Monika Sosnowska "1:1”, 2007 Download

1:1

Monika Sosnowska

Monika Sosnowska studies architecture from the point of view of its failures, she is interested in places encumbered with error, knocked out of functionality, in absurd ideas and absurd implementations. Her works are often peculiar mementos of architectural utopias brought out from the past, inspired by architecture’s psychedelic properties. The main reference point for Sosnowska are the experiences of post-war modernisation – the all-too-familiar to the inhabitants of Eastern Europe landscape of housing blocks, service pavilions, train stations and shopping centres. What is particularly important for the artist are this architecture’s secondary attributes, such as the muted colour range dominant in Poland of the 1960s and 1970s, the peculiar ‘modern’ building materials, but also the grassroots activity of the blocks’ inhabitants: redesigning the corridors to win storage space, erecting fences, creating amateur signboards and shop windows. The concrete legacy, rooted in the provisions of the Athens Charter, is the source of inspiration and quotation in many of Sosnowska’s works.

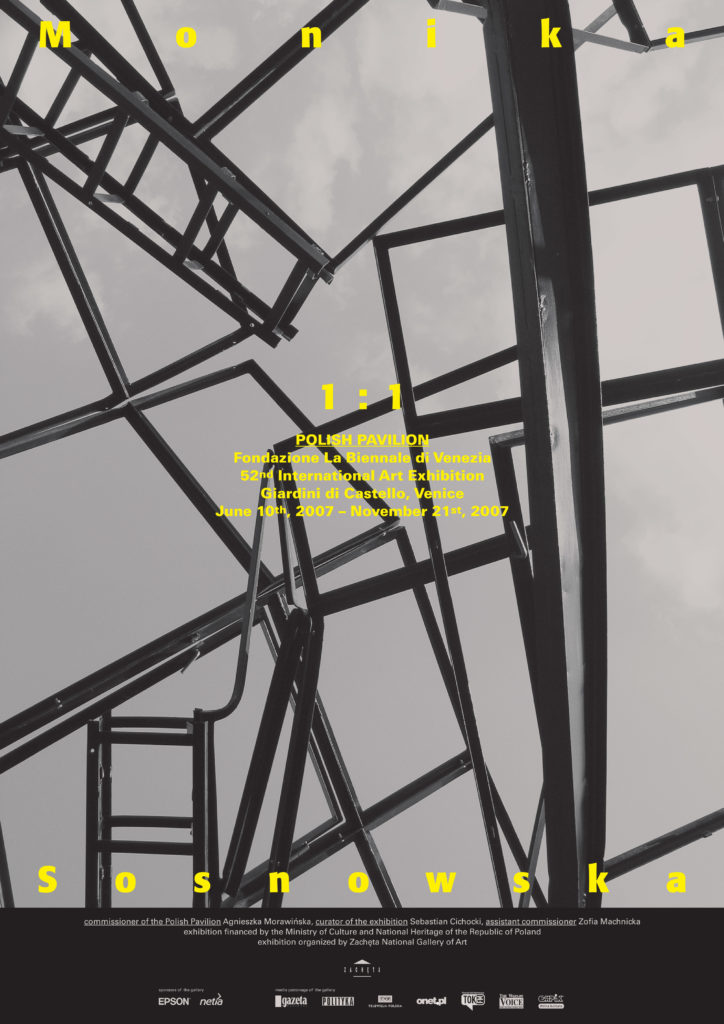

The artist’s latest project, called 1:1, is not, however, a nostalgic return to communist Poland’s favourite architectural solutions but rather the consequence of a reflection on the post-war architectural concepts analysed from the angle of the local, Eastern European, surprisingly vital mutation of the International Movement. During the People’s Poland era, progress was often restricted to impulsive, rash (and often absurdity-producing) modernisation. The requirement of ‘modernity’ in post-war Poland was a top-down imposed decision, controlled through a series of orders. In order to meet the adopted targets, contractors had to build quickly, in a slapdash manner, and in accordance with the official design requirements. Living among microscopic bathrooms, blind kitchens, crooked walls, purposeless alcoves, labyrinths of pipes leading nowhere and rolling parquet floors became the daily reality for the inhabitants of the sprawling housing developments. The artist decided to use an important part of the former building infrastructure (Fabryka Domów Mieszkalnych, or the Housing Block Factory) to erect an experimental sculpture devoid of the burden of functionality.

Today, modernist buildings in Poland, as elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, are being modified. In the contemporary realities, governed by the brutal laws of the free-market economy, the coarse charm of the past decades’ architectural ‘ballast’ is being laboriously painted over. The practice has become widespread of ‘repackaging’ unattractive buildings, and new facades are often erected to conceal earlier structures. Many important post-war architectural works in Poland have been slated for demolition, such as the Supersam department store in Warsaw (opened 1962), one of the era’s most notable designs. Some highly industrialised regions, such as Upper Silesia, are today turning into cemeteries of post-industrial structures, remaining since the 1990s in a state of semi-decay.

In a number of recent works Monika Sosnowska transgressed the, more or less artificial, border between contemporary and architecture. In her own words:

‘It seems to me that what I do is somehow in opposition to what architecture stands for. I also think that my art is a completely different discipline, even though I focus on the same problems as architecture does: the forming of space. Utilitarianism is architecture’s fundamental attribute. Architecture organises, introduces order, reflects political and social systems. My works introduce chaos and uncertainty instead’.

Uncertainty is also an irremovable part of the latest project. The additional structure emerging in the Polish Pavilion is almost organic – it ‘parasitises’ the almost 70 years older exhibition venue. The installation 1:1, like Sosnowska’s other works from the last couple of years, can be viewed as a reference to the practices of the artists of the 1970s (G. Matta-Clark, R. Smithson and others) and a continuation of the reflection on decay and destruction, but also as a criticism of the art institution via a radical intervention in its architectural tissue. After all, the project serves to ‘exhibit’ the Polish Pavilion itself – a building representative of the 1930s, which, as one of the work’s elements, ‘wrestles’ with another construction growing out from inside it. Sosnowska’s project fits both the local context and the global discourse on the search for functionality, on moving away from modernism’s stylisation and pro-community tasks. Even though Minoru Yamasaki’s blocks collapsed on July 15, 1972, it seems that the modernistic dream, this multifaceted social project, has not yet been dreamed to the end.

- YEAR2007

- CATEGORY Biennale Arte

- EDITION52

- DATES10.06 – 21.11

- COMMISSIONERAgnieszka Morawińska

- CURATORSebastian Cichocki