Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers

Katarzyna Krakowiak

Katarzyna Krakowiak’s sound sculpture Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers is the amplification of the Polish Pavilion as a listening-system. Rather than creating a new space, the artist’s proposal for the Architecture Biennale takes an empirical turn, taking the existing interior as its point of departure, with all its deficiencies and imperfections guiding the work. The art is in the “naked building”—presented through sculpture as a complex sonic process that generates, transforms, and transmits sound. Studies in the natural acoustics of the Polish Pavilion offer several ways to perform the amplification process. Architectural micro-deformations of the building’s walls and floor, the renovation of the ventilation system, and reinforcement of the resonant frequencies serve to bring this latent acoustic experience to the fore. The focus is on the secret but audible knowledge inscribed in the niches, apses, bays and vestibules, full of long-acknowledged deficiencies and forgotten paradoxes. None of the sounds in the Pavilion are alien to the building. They are all always already there. Yet, once amplified, the familiar ambient sounds become alien themselves. Beyond the visual and the material, they compel us to hear what was always there—the others just outside the walls. Hence, the real subject of the work is essentially the entire architectural complex that is home to four other pavilions: Egypt, Romania, Serbia, and Venice.

1. Reverberation and Resonant Frequencies

Acoustic measurements performed by Andrzej Kłosak revealed the Pavilion’s strong reverberation, lasting over 6 seconds. In the empty room, measuring less than 200 m², human speech is on the threshold of what is recognizable—even three meters from the source. It is due to the interior’s excessive reverberation rather than insufficient volume of human speech, that public openings staged inside the Pavilion typically require a PA system. To pinpoint this acoustic effect, the resonant frequencies of the Pavilion’s main hall are reinforced, further diminishing the recognition threshold of speech—and thus making even regular conversation difficult.

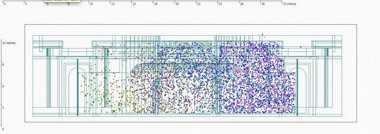

The building’s materials (brick walls, marble floor) as well as the symmetrical, rectangular form of the interior cause the sound to reverberate endlessly as it is reflected vertically. In such cases, sound sources are practically untraceable. Voice seems to be coming from everywhere, even if the speaker is standing just a meter behind one’s back. To enhance the experience of being immersed in sound, the floor and one of the walls are tilted at a slight angle. The introduction of a different material (a wooden floor) and the incline itself will also influence sound propagation. With 50 sound sources, the interior of the Polish Pavilion will take the visitor to the heart of an unknown, unfathomable realm of sound.

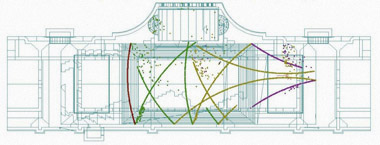

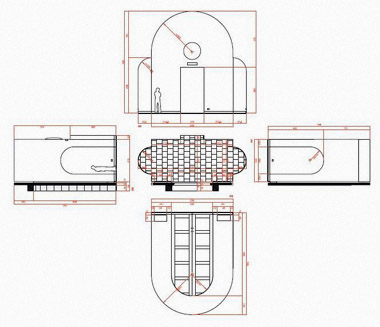

The central elements of the sculpture are the surfaces, designed based on a reverberation model depicting which sound waves are reflected and propagate inside the Pavilion (to the right-hand side in the above picture).

Simulation of wave propagation (horizontal plane), 2012, part of the acoustic model by Andrzej Kłosak © Katarzyna Krakowiak

The tilting of the floor and wall (architectural design by Katarzyna Krakowiak, based on the architectural plan of the Polish Pavilion prepared by Marcin Kwietowicz)

Simulation of wave propagation, 2012, part of the acoustic model by Andrzej Kłosak © Katarzyna Krakowiak

2. Ventilation System

Katarzyna Krakowiak dismantled the existing artificial ceiling—which was mounted for the few last exhibitions to cover the skylight and ventilation system—in order to streamline the air trajectories. One of the main discoveries during research into the Polish Pavilion was that words uttered on the roof, reaching the interior through ventilation holes, are much more understandable that those at floor-level. In this way, the ventilation system opens the pavilion both to the surroundings of the building, as well as to other pavilions. For the sound sculpture, ventilation pipes are used to bring sounds traveling with the air from adjacent pavilions into the Polish one.

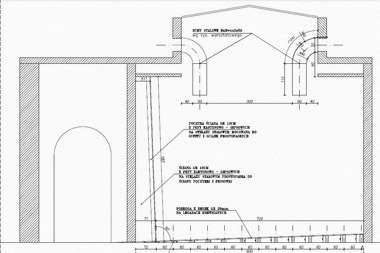

Opening of the ventilation holes under the ceiling (architectural plan of the Polish Pavilion prepared by Marcin Kwietowicz)

3. The Niche, the Vestibule and the Walls

The acoustic probing of the pavilion revealed a plastered apse, located right opposite the main entrance. Now it is presented in full view and restored to its original acoustic function, that is, to reflect the sounds appearing in the vestibule. The vestibule itself is a transition area between the exterior and the interior of the pavilion. To mark this process of transition—no more than a few steps—the passage is soundproofed, drowning out the ambient sounds and thus emphasizing the acoustic function of the vestibule, as well as preparing visitors to experience her sculpture aurally.

The final gesture was to stage a “live sonification” of the vibrations of the walls of the entire building. The trembling of the walls is translated into sounds, and made audible in the space of the pavilion together with the trembling of selected parts of the building. A network of sensors and cables entwines the entire architectural complex, including the façades of the adjacent pavilions, marking the continuity of sound as a phenomenon.

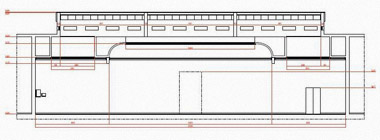

Vestibule (architectural plan of the Polish Pavilion prepared by Marcin Kwietowicz)

- YEAR2012

- CATEGORY Biennale Architettura

- EDITION13

- DATES28.08 – 25.11

- COMMISSIONERHanna Wróblewska

- CURATORMichał Libera

Idea

“Yes, it could begin this way, right here, just like that, in a rather slow and ponderous way, in this neutral place that belongs to all and to none, where people pass by almost without seeing each other, where the life of building regularly and distantly resounds. What happens behind the flats’ heavy doors can most often be perceived only through those fragmented echoes, those splinters, remnants, shadows, those first moves or incidents or accidents that happen in what are called “common areas,” soft little sounds damped by the red woolen carpet, embryos of communal life which never go further than the landing. The inhabitants of a single building live a few inches from each other, they are separated by a mere partition wall, they share the same spaces repeated along each corridor, they perform the same movements at the same times, turning on a tap, flushing the water closet, switching on a light, laying the table, a few dozen simultaneous existences repeated from storey to storey, from building to building, from street to street. They entrench themselves in their domestic dwelling space—since that is what it is called—and they would prefer nothing to emerge from it; but the little that they do let out… ”

On the Stairs, I by Georges Perec is a fragment of: Georges Perec, Life a User’s Manual, translated from the French by David Bellos, reprinted by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc. and The Random House Group Limited for The Harvill Press. Copyright © 1978 by Hachette Littérature, translation copyright © 1987 by David Bellos

Architecture is built of sound. It is what makes the diffusion of sound possible—absorbing, filtering, and transferring it, amplifying some of its components at the expense of others. Enclosed spaces are room tones, while niches are specific echoes. The ventilation and heating systems are a quiet yet constant noise, whereas windows and walls are the filtered sounds of street bustle, the buzzing of cicadas, or neighbor’s living rooms. The sound-houses which Francis Bacon foretold in his New Atlantis, the ones with new quarter-tone harmonies and artificial echoes, “reflecting the voice many times” and giving “back the voice louder than it came,” transporting it with “trunks and pipes”—they are all here, forming our natural environment. We live, work and play in gigantic complexes of sounds—their distribution is what we call architecture.

From the famous lines by Vitruvius to critical essays by Steen Rasmussen and Juhani Pallasmaa, from Baroque composers to Alvin Lucier, from Francis Bacon to Charles Dickens and Bohumil Hrabal, in the long tradition of writing about architecture there is a constant undercurrent of listening to architecture. It is a complex discourse with insights as varied as listening in, listening through and listening to, or perhaps of, architecture. However, with the rise of knowledge in acoustics since the nineteenth century, we can also consider architecture as a listening-system in itself. It is a specific medium, channeling and transforming the sounds which eventually reach our ears. What we hear is already mediated by architecture and depends strongly on its materials, forms and functionalities.

By the same token, architecture becomes a subtle, invisible way of organizing our social life. Sound-wise, walls, floors, ceilings, heating and air-conditioning systems are all a means of connecting and transforming social relations. They do not divide. Rather, they form an invisible common ground beyond the material and the visual; a sonic plane of performing “the social” in everyday practices: such as hearing, listening, or eavesdropping. Generally subtle, at times uncomfortable—the presence of this sphere is what structures our communities.

Architecture as a system of listening to others brings us to a position of hearing too much or too little, being heard too much or too little, willingly or not, but definitely beyond our intentions. We are constantly hearing others and we are constantly being heard. These are the moments where the modern promise of “assigning private space” is transformed into a more ambivalent, and truly reciprocal “participation in private spaces.” Something in-between “the private” and “the public.”

As Georges Perec put it, “they would prefer nothing to emerge from it; but the little that they do let out…”

Michał Libera, Exhibition Curator

Authors

Katarzyna Krakowiak

Born in 1980, explores sculpture and architecture with the use of various media, notably sound. In 2006 the artist graduated from the Sculpture Transplantation Studio, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań, under Mirosław Bałka, where she worked as assistant from 2004 to 2007. Significant exhibitions include Who Owns the Air?, Galeria Foksal (Warsaw, 2011), Game and Theory, South London Gallery (London, 2009). Her works were presented in group exhibitions at, among others, KUMU Museum (Tallinn, 2011) and HMKV (Dortmund, 2011). In 2007 she completed an internship at the Architecture Foundation, London. Since 2011 she has been working at the Studio Urban Interior Design

(Department of Interior Design) at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk (in collaboration with Jacek Dominiczak). Working with Krzysztof Gutfrański as part of the Ekspektatywa series (Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, 2010) she has prepared and published a manual for constructing your own Metaphones.

Michał Libera

Born in 1979, sociologist, producer, curator, and music critic. Co-founder of 4.99 Foundation, organiser of concerts, workshops, and rehearsals of, among others, Playback Play, plain. music, The Song Is You. Co-producer of a series of albums devoted to the Polish Radio Experimental Studio and released by Bôłt Records, as well as a series of conceptual pop albums Populista. He has collaborated with Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw; Centre of Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw; Dunikowski Sculpture Museum in Królikarnia, Warsaw. In the years 2007–2011 he presented a number of programmes about contemporary music on Polish Radio (Channel 2). Since 2001, he has been the editor of a musical series launched by the publishing house słowo/obraz terytoria. His critical essays have appeared in, among others, “Glissando”, “ResPublica”, “Kultura Współczesna”, “Recykling Idei”, a collected volume of his texts will be published in 2012 by Krytyka Polityczna.