Selected curated and co-curated exhibitions: Politics of Collection, Collection of Politics, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (2010); The Real War, solo show with Sean Snyder, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon (2010); Evil to the Core, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon (2009–2010); Never Looked Better, Beth Hatefutsoth, Tel Aviv (2008–2009); Chosen, a joint collaboration between Wyspa Institute of Art, Gdańsk and The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon (2008–2009); Mobile Archive, in collaboration with Hamburg Kunstverein; Liminal Spaces, traveling seminar, Israel and Palestine (2006–2008); People, Land, State, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon (2006); This is Not America, Art Project Gallery, Tel Aviv (2006).

… and Europe will be stunned

Yael Bartana

The exhibition … and Europe will be stunned will be the official Polish participation at the 54th Biennale of Art in Venice in 2011. This video installation by the Israeli-born artist Yael Bartana will be the first time a non-Polish national has represented Poland in the history of the Biennale. Bartana’s three films Mary Koszmary (2007), Mur i wieża (2009) and Lit de Parade (2011) revolve around the activities of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP), a political group that calls for the return of 3,300,000 Jews to the land of their forefathers. The films traverse a landscape scarred by the histories of competing nationalisms and militarisms, overflowing with the narratives of the Israeli settlement movement, Zionist dreams, anti-Semitism, the Holocaust and the Palestinian right of return.

Mary Koszmary (Nightmare) is the first film in the trilogy and explores a complicated set of social and political relationships among Jews, Poles and other Europeans in the age of globalisation. Using the structure and sensibility of a World War II propaganda film, Mary Koszmary addresses contemporary anti-Semitism and xenophobia in Poland, the longing for the Jewish past among liberal Polish intellectuals, the desires of a new generation of Poles to be fully accepted as Europeans and the Zionist dream of return to Israel. The second film in the trilogy Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) was made in the Warsaw district of Muranów, where a new kibbutz was erected at actual scale and in the architectural style of the 1930’s. This kibbutz, constructed in the centre of Warsaw, was an utterly ‘exotic’ structure, even despite its perverse reflection of the history of the location, which had been a part of the Warsaw Ghetto. In the new film Lit de Parade, the final part of the trilogy, Bartana brings the notion of national identity, representation and participation to the ultimate test. The plot evaporates all borders between truth and illusion, reality and fiction and calls for a confrontation with our own self understanding of the definitions and perspectives of contemporary culture and society. It leads the viewer into a state of uncertainty about whether the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland is pure hallucination, an artistic project, or rather a concrete and constructive possibility for the near future of Poland, Europe and the Middle East.

The whole trilogy of films can also be read in a broader context. Apart from the complex Polish-Jewish relationship, it is an experimental form of collective psychotherapy through which national demons are stirred and dragged into consciousness. This is a story about our readiness to accept the other and of assimilation in an unstable world where geography and politics are subject to radical shifts.

The films are screened inside a complex exhibition design (architect: Oren Sagiv), that will fill the whole interior of the Polish Pavilion. The built volumes inside will evoke associations with a settlement or outpost.

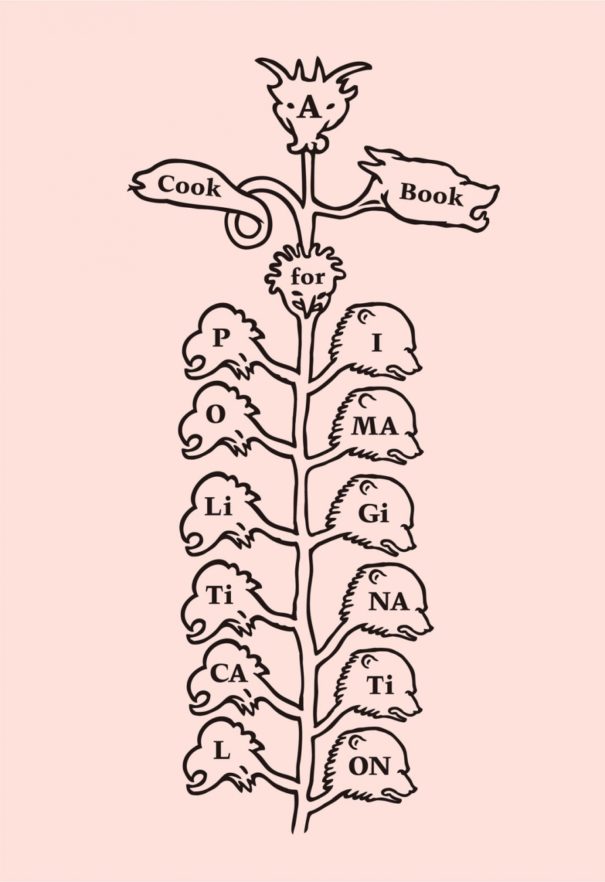

The publication A Cookbook for Political Imagination will be produced to accompany the exhibition. This is not a traditional exhibition catalogue but a manual of political instructions and recipes, covering a broad spectrum of themes and written by multiple authors.

- YEAR2011

- CATEGORY Biennale Arte

- EDITION54

- DATES04.06 – 27.11

- COMMISSIONERHanna Wróblewska

- CURATORSebastian Cichocki, Galit Eilat

The Authors. Biography

Artist

Yael Bartana was born in 1970 in Kfar Yehezkel, Israel. Her artistic practice includes film, photography, video and sound installation. She has had numerous solo exhibitions,. e.g. at PS1, New York’ Moderna Museet, Malmö; Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv; Kunstverein, Hamburg; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, or Fridericianum, Kassel.

She has also participated in such prestigious group shows as Manifesta 4, Frankfurt (2002); 27th São Paulo Biennial (2006) or documenta 12 in Kassel (2007). In her Israeli projects, Bartana dealt with the impact of war, military rituals and a sense of threat on everyday life. Since 2008, the artist has also been working in Poland, creating projects on the history of Polish-Jewish relations and its influence on the contemporary Polish identity. Yael Bartana is a winner of numerous prizes and awards, e.g. Artes Mundi 4 (Wales, 2010), Anselm Kiefer Prize (2003), Prix Dazibao (Montreal, 2009), Prix de Rome (Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, 2005), Dorothea von Stetten Kunstpreis (Kunstmuseum Bonn, 2005) or the Nathan Gottesdiener Foundation Israeli Art Prize (2007).

Curators

Sebastian Cichocki works as the chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Between 2005–2008, he worked as director of the Centre for Contemporary Art Kronika in Bytom, Poland. In his curatorial and publishing projects, he often refers to the land art and conceptual traditions.

Selected curated and co-curated exhibitions: Early Years, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2010); Daniel Knorr. Awake Asleep, Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw (2008); Monika Sosnowska. 1:1, Polish Pavilion at the 52nd International Art Exhibition, Venice (2007); Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska. Oskar Hansen’s Museum of Modern Art, CCA Kronika, Bytom (2007); Bródno Sculpture Park, Park Bródnowski, Warsaw (2009–2011); Warsaw in Construction, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, public space, Warsaw (2009, 2010). Author of critical texts and art-related literary fictions. Chief editor of the humanities quarterly Format P. He has published in periodicals such as “Artforum”, “Cabinet”, “Mousse”, “Krytyka Polityczna”, “FUKT”, “Muzeum”, “Czas Kultury”, “IDEA arts+society”, “Camera Austria”.

Galit Eilat is a writer, curator and the founding director of The Israeli Center for Digital Art in Holon. She is co-editor in chief of Maarav — an online arts and culture magazine, as well as research curator at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Her projects tackle issues such as the political situation in the Middle East, activism or political imagination in art.

Galit Eilat and Charles Esche talk to Yael Bartana

Dear Reader,

Below is the edited transcript of a series of conversations between Yael Bartana and the curators Galit Eilat and Charles Esche. The conversations took place over several days in Eindhoven/NL at the time of Yael Bartana’s participation in Play Van Abbe/Strange and Close at the Van Abbemuseum. The transcript begins in the middle of a meditation on the impact of Israeli — and other — societies on the individual imagination, and the necessity of finding a position outside one’s home in order to reflect upon it.

Galit Eilat: …It’s a part of the collective narrative in Israel, and it’s hard to ask questions about this narrative from inside the country. I think that when Yael left the country, when she took some distance from it, it became possible for her to look at herself and the society of which she was a part. You don’t see yourself as different from the society in which you grow up, so when you leave it, it’s like looking at yourself in the mirror, like the Lacanian mirror stage. You start to see yourself separated — from your mother and from the world. But in Israel, there is an extra step of separation: from the nation, because in Israel, the nation is really like a family.

Yael Bartana: I think the trauma is not just individual, it’s collective. If something bad happens, then it is seen as collective punishment. It’s no longer the individual…

Galit Eilat: It’s always collective trauma. We are one body.

Charles Esche: But I have to say that I recognize this from my own biography, too. There’s a profound difference in the conversations you can have with someone who has lived his or her whole life in the Netherlands and somebody who hasn’t. When I was in Sweden, I felt the same thing. I mean, I understand the exceptionalism of Israel, but…

Yael Bartana: No, it’s not special for Israel; it’s true of every society. Eva Hoffman said that every immigrant is an amateur anthropologist. You’re always an outsider as an immigrant; you look at society in a different way. The same thing can partially happen when you step outside of your own nation and then look back at it. When I was about twenty, I experienced this in another way, when somebody from my family refused to serve in the occupied territories. At that time He was serving as an an office in Jenin, when he decided that he can’t do it anymore. He was convicted 4-month captivity and I had to drive him to jail.

Charles Esche: Did you experience this new perspective as a liberation or as a trauma? As though suddenly you needed to criticize something you didn’t have to criticize before?

Yael Bartana: First of all, I felt privileged, because I have a place to put my feelings: in my work. I think any creative person would deal with it like this, and in that way, I’m lucky. Lucky, but then again, I suffer because I’m trapped in between. That is, it is you’re home, you cannot be free of it, but you’re constantly criticizing it, aware that you don’t want to represent what it stands for. If you come from Israel, you are often seen as its ambassador, and you have to be very clear about your position.

Charles Esche: I think that in my life, it has become increasingly difficult to feel represented by a democratic government. This is partly because we all move through different countries but also because, ever since the recent wars that the British government has involved “me” in, it is not so simple to feel that the government on my passport represents me in any way. The wars are not politically or ideologically justified; they are national or Western crusades. Yet I can hardly just choose a better nationality. Maybe that’s another way in which Israel is a kind of laboratory of the former West. Today, politics is more defined by nationality or culture than by ideas, and you cannot change your nationality or cultural background as easily as your mind.

Galit Eilat: What you’re describing is quite interesting, because you take responsibility for your state. It means that you are a citizen, and that you recognize the state as an authority, as an entity.

Charles Esche: For sure, which is maybe different in Israel. The works that interest me from Israel are very conscious of their position with relationship to the state. I don’t think that’s true for the vast majority of British or Dutch artists, even the interesting ones. Yael was describing how, in her education, people ignored the fact that they were Israeli and aligned themselves with some universal Western art history. I think that became increasingly unsustainable in Israel, but it is also unsustainable here in Europe.

Galit Eilat: But both you and Yael are doing the opposite by accepting the nation-state, by accepting the situation and the responsibility that comes with it. However, why should we accept the nation-state? We are, in general, against the nation-state. So why do we take the responsibility and the blame for it? When in another situation we might say, “The old system is over. We want to build a new system,” when it comes to guilt and responsibility, we feel like citizens. It’s a question of identification: when you take responsibility, it means that you are identifying yourself with something. You don’t take responsibility for something you don’t identify with.

Charles Esche: I think there’s a kind of mythology of cosmopolitanism, and on a certain level, this myth operates in the art world. We can all work in the same institution and none of us are Dutch and this doesn’t interfere much with our working lives.

Galit Eilat: At least we would like to see it that way.

Charles Esche: Yes, perhaps we’re kidding ourselves. But once you step outside of this little world, which has permitted a bit of cosmopolitanism, and look at immigration politics or education or military decisions, you see the nation-state is absolutely present. Then this idea of some breakdown of the nation-state looks laughable. Twenty years ago, there seemed to be more of a possibility for international cooperation than there is now.

Galit Eilat: Yes, but the British passport is not you — and this is also a question for Yael: Why, then, do you have this over-identification with the state? For example, your last work Wall and Tower is about the establishment of a state — not just the Israeli state, but the state in general. You build a wall, and you build a tower — and establish yourself!

Yael Bartana: Establishment and its consequences. What happens after the establishment—

Galit Eilat: Yes. But you didn’t address any other kind of establishment. You address a very specific establishment: a state with a flag. And this seems like over-identification, repeating the rituals that you criticize.

Yael Bartana: I’m not repeating. That’s not true. True I am repeating or even mirroring the mechanism.

Galit Eilat: You’re documenting?

Yael Bartana: In the past, I never documented the actual ritual. I always document the side effects. For example in Trembling Time, I documented the complete halt of traffic on a roadway during the minute the commemoratory siren sound and not the military and state ritual. Wall and Tower is staged.

Galit Eilat: But with Wild Seeds, you almost create a ritual, or at least you make something that is basically a children’s game into something else that marks a historical moment. It even takes its name from a particular Gaza settlement — Gilad’s settlement. Is Wild Seeds a kind of pivot point in the work?

Yael Bartana: Yes, in the sense that the camera does not just document but rather actually creates the situation. Wild Seeds is the first work in the exhibition, which feels like a statement.

Galit Eilat: Can Wild Seeds be seen as your self-portrait?

Yael Bartana: Hmmm, I am too old! I do feel connected to this generation. I feel empathy for them. They’re so young and so sharp. They’re a step ahead in their ability to understand, and to see the kind of mistakes that are being made. Wild Seeds is almost like a parody of what they do, because they understand the system; they understand that something is going wrong and they “flip” it. I think the work mostly refers to the third generation, one that is not very connected to a straightforward Zionist heritage or the spirit of the ideology, or to what it meant to build a country from scratch, what it meant to resist the British mandate. The second generation experienced a series of wars. Then came the third generation: they are much more interested in globalization. For them, Israel is not such an island anymore. They travel from an early age, so they are potentially much more open. They’re more educated in the sense of having seen other movements of resistance, and I think they have different sensibilities toward society — I’m not saying all of them do; we have to remember this is a particular group of kids who are privileged and supported by their parents — but still, they play this game with a high awareness of what they are doing.

Charles Esche: Just to clarify, Wild Seeds is a real game that these kids play, based on the media coverage of the evacuation of the Jewish settlements in Gaza. You then set up a group to play the game while you filmed. Is that right?

Yael Bartana: Yes.

Charles Esche: But it is also a very sexy film. They treat the politics with a beautiful playfulness. Sometimes it seems that the politics become a vehicle for this very close contact with each other.

Yael Bartana: Where else in the world you would have such a weird game to get close to each other? It’s connected to the settlement idea, but it is also a mechanism to resist the police, the authorities.

Galit Eilat: It reminded me of the first time that I was sitting on the road with young Israelis, young Palestinians, all of us in very close bodily contact. We were fighting for an idea, but we all were sitting in two or three rows, hugging each other.

Yael Bartana: I think Wild Seeds is really a game about building community. The kids didn’t know each other before, but immediately they have an enemy, someone to resist, and they unite really quickly. And that’s what’s happened. I introduced these people to each other and I said, “You’re all going to play this game and get to know each other”. And then, in no time, they became a group that was playing against the authorities. Suddenly, they were in the middle of a collective experience.

Galit Eilat: This will happen with the resistance, you know — you have somebody to resist, so you become one body.

Yael Bartana: It’s social and self-made, though, instead of the state creating this ritual. It’s a self-made way to connect to each other. The strange thing is that some settlers felt that this was a portrait of their lives while others really got upset — the “stupid-leftists-they-don’t-know-anything” attitude.

Charles Esche: I can imagine. But how did you feel about the settlers seeing it as a portrait of their lives?

Yael Bartana: I found it amazing. It becomes more about the politics of human behavior, how people function. I like the idea of wild seeds as seeds that are not able to grow on cultivated land. They plant themselves and decide where they grow. This could be the third generation of peace activists, but also the unwanted Gaza settlers.

Charles Esche: Why did you separate the subtitles from the image?

Yael Bartana: Because I wanted to force the viewer to decide what to look at — the game or the language. You’re much more intimately engaged in the physicality of the film. Sometimes I really like the text without the image, because then you must try to imagine what you would see.

Galit Eilat: But you can read body language, too. It’s stronger, I think, than the written language.

Yael Bartana: But you know that the subtitles are not a literal translation. They have their own logic, their own order and meaning. For a Hebrew speaker, this is obvious, but I also wanted it to work for those who don’t speak Hebrew; that’s why I separated the subtitles.

Galit Eilat: The idea of ritual reoccurs in A Declaration, this strange act in which you filmed and act of removing a the Israeli flag and replacing it with a planted olive tree.

Yael Bartana: Why is this strange?

Charles Esche: Because it’s a ridiculous island, no? So small and lost in the Mediterranean with this sad flag waving…

Galit Eilat: I find it very expressive. Yael lived on the sea; she saw this island and the flag and thought, why not replace the flag with an olive tree.

Yael Bartana: It’s a very emotional piece for me, an expressive piece. Walking on the pedestrian promenade next to the beach and arriving in Jaffa and seeing this flag out to sea… It made no sense to me. The work is a reaction, in fact. It’s what I think everybody should do if they don’t like something; they should do something about it. Many Israelis are really upset when they see this work.

Charles Esche: Because you took the flag down.

Yael Bartana: Of course, the holy flag. How dare I touch the flag! A collector from Holland bought the work. He’s Jewish and American, but he’s proud of this piece.

Galit Eilat: Because he associates the olive tree with peace?

Yael Bartana: No, I think he understands exactly what it means, but he found that it was a good suggestion — to denationalize.

Charles Esche: Yeah, but the olive tree has almost become a national symbol, no? For Palestine, and that’s a —

Yael Bartana: It is, but it can be read in two ways.

Charles Esche: Okay. But you ridicule the idea, claiming this stupid little rock for a nation, be it for Palestine or Israel. It’s nicely ridiculous.

Galit Eilat: It is not just any rock. It’s called Andromeda. It’s already like a statement built on this idea of a mythological story of sacrifice and rescue.

Charles Esche: And then there is this beautiful specimen of humanity doing the action, the boy who goes out to the island. Did you choose him specifically?

Yael Bartana: Well, he’s a seaman; not every person could do what he does. You really have to know the sea to understand when to row and how to dock. And he knew all the police, because you cannot just remove a flag. He assured them, “It’s ok, it’s ok, it’s on me, I’ll take care of it.” So they left us alone and we could film the action.

Charles Esche: You see his power. You know, maybe it becomes another kind of ritual…

Galit Eilat: No, it’s not a ritual — it’s related to an author, to a gesture.

Yael Bartana: It’s a concrete, physical and direct act and proposal to take the flag down and plant the olive tree . It’s not just the gesture. In this way, it’s like Summer Camp, which also has a concrete element of actually restoring a Palestinian home.

Galit Eilat: Summer Camp began when you met Jeff Halper, correct?

Yael Bartana: Yes. I met Jeff Halper [Founder of Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, or ICAHD] through you in “Liminal Spaces.” I’d wanted to make a piece about a house for a long time, so I contacted him and explained that it wasn’t going to be a documentary about his activities, but an artwork where I would compare his work to a Zionist ethos. I was very transparent. I didn’t want to do a film that would be a surprise in the end. I interviewed him to get to know a bit more about his activities and his personal background—how he initiated the committee and so on. He’s an American Jew and he studied anthropology. He’s driven by this notion of “facts on the ground” and a desire to make things visible. Reconstructing a house is very visible and it also shows how many houses need to be rebuilt. ICAHD always does this action in collaboration with local communities, so it’s not as if they come from the outside and decide, “We want to be good citizens. We want to resist the state by doing this.”

Galit Eilat: From Summer Camp on, building really becomes a part of your work, but building as a point of resistance. Usually building is something that is for the future. But, in this case, it’s kind of the opposite.

Yael Bartana: That’s what’s so fascinating for me about this organization: the act of resistance is something constructive. Normally, resistance evokes destroying, breaking down a house…

Charles Esche: But it is also simply about making one’s mark on the earth, on the world, on the canvas, or whatever, isn’t it?

Yael Bartana: I think one of the things that I’m interested in is how you can take an ethos, for example, or a symbol, and turn it upside down. You take the same ethos of Zionism and you flip it—flip it so that it works against the same mechanisms that constructed it.

Galit Eilat: Is this why after Documenta you started showing your film together with Avodah?

Yael Bartana: I felt like I needed to give more context to the film. And then I slowly came to the solution of showing the two films back to back. Maybe it can be read as didactic, but the reference to the work is clear: I’m showing you what happened in the ’30s when Zionism wanted to create a belief that you can build a home on the land of Palestine (the reason the film was made was to recruit people to build Israel). Summer Camp uses the same ethos but with a different meaning.

Charles Esche: The ideology of Avodah is an ideology of resistance. It starts with this strange, dramatic music, the word “Palestine” and this British flag. In this way, it speaks about occupation, about imperialism, about domination, about a clearly foreign force. You know “Palestine” and the British flag. At that time, Zionism was in favor of liberation. It was an emancipatory movement that became, through a long history that we don’t have to go into here, something else. It started with these high hopes: the kibbutz, socialism in Israel, new land and a new architecture and society — an experiment for which I still have a huge amount of respect. Of course, at the same time, ethnic cleansing was part of the foundation of the state, and so for a long time there was an ambivalence about Israel. In the recent past, with Lieberman, the Gaza war and so on, this ambivalence has completely disappeared. It was dream-nightmare that became just a nightmare.

Galit Eilat: Yael is now reading Altneuland, Theodor Herzl’s story, you know? People usually refer to Herzl as the founder of Israel, but the book is really a novel, a kind of fiction that became fact. Unfortunately, few people are reading Altneuland today in the spirit in which it was written.

Yael Bartana: I realized that, looking at the film, you can recall that it’s connected to a historical moment because of the music and editing and the style. But if you are not interested in Israel, you could take it perhaps as an act of settlers in general.

Charles Esche: Why this particular film?

Yael Bartana: Avodah was just a fascinating film, so beautifully made but with a brutal relationship to the land. You see the influence of German and Soviet cinema as well, which might lead you to question the uniqueness of the whole Zionist movement and how much it is connected to other movements at the time.

Galit Eilat: At this time, most of the filmmakers came from Poland to Israel.

Yael Bartana: Helmar Lerski, the maker of Avodah, is Swiss. He also worked on Metropolis. You can see in his camerawork his understanding of light. His way of sculpting the figures in light is something that I think is still amazing today.

Galit Eilat: Yes, of course, you gave up on Riefenstahl, so—

Yael Bartana: I gave up on her?

Galit Eilat: Yeah, you gave up on her so you found—

Yael Bartana: I never gave up on Riefenstahl…

Charles Esche: So, what made you move from the foundation myths of Israel to Poland? Why Poland first?

Yael Bartana: I think it is very much connected to Israel, but I wanted to create a new laboratory. A new place to explore, experiment What I initially felt is that Poland and Israel have a lot in common. We have to deal constantly with our reality and history; so does Poland. Perhaps many other places do, too, but these issues are quite specific in Poland. So many Jews had lived in Poland since the 15th century. And I have to say that when I went to Poland, I felt very connected to the place on some strange level. It’s something I never felt in the Netherlands or in Sweden.

Charles Esche: What about in America?

Yael Bartana: In America, on some level, yes, but in a different way. In Poland, it was a really deep, metaphysical, emotional link. I could feel the place. If I couldn’t feel connected on that level, I wouldn’t have stayed there working for four years. There was something there that attracted me so much that I really wanted to open all the wounds. On an intellectual level, it was also about knowing that this place was used by the state of Israel to such a large extent. It was connected to this whole machinery of Zionism and the Holocaust.

Galit Eilat: I think Polish artists also relate to this question quite a lot of work by Arthur Żmijewski or Pawel Althamer that reflects on the Israeli question.

Yael Bartana: and the Jewish question.

Charles Esche: Yes, on the Jewish question. How Poland deals with that question of loss, which is a European loss. You know, this absence is a gaping wound even in Eindhoven. But it is not really addressed in the old Western Europe.

Yael Bartana: Once I talked about it with joanna Mytkowska and Andrzej Przywara at Foksal Gallery, I felt like the floodgates came open instantly (snaps fingers). The discussions went on night and day. It was really an amazing reaction. And when I said I want to make a propaganda film asking the Jews to return to Poland, Both Joanna and Andrzej were completely taken by the idea. It was fascinating to see such an immediate reaction. I started to learn about the Polish intelligentsia, who are so occupied with this absence. They feel a real need for Jewish culture, which I didn’t know was the case before I started to work on the piece.

Charles Esche: Then you met Sławomir Sierakowski from “Krytyka Polityczna” who appears in both “Polish” films.

Yael Bartana: Yes, and once again, we made an instant connection. We met in the morning in a cafe, and we fell in love. I saw this young man coming, and I was completely shocked. He’s so smart, this guy, and it really didn’t take much to get us going. We came up with this slogan: “Three million Jews can change the life of forty million Poles”.

Charles Esche: He wrote the text for Mary Koszmary, right?

Yael Bartana: He and Kinga Dunin. (She’s an activist with a background in literature, and she’s also connected to “Krytyka Polityczna”) It was a long process, but eventually I asked him to be the writer. I told him a few things I wanted to talk about, and then he came up with the text because he also believed in it; otherwise, he wouldn’t have performed it so well. He understands his position and how to perform to the camera.

Charles Esche: I often show the film in lectures and there’s always a silence that falls after it finishes. You just can’t talk immediately after it; you have to simply take it in. There’s very few videos, or artworks, or even films that I know that generate this sort of reaction: What actually happened? What does the ambiguity mean?

Yael Bartana: The speech is in the tradition of propaganda and pedagogical speeches — very emotional, using the techniques popular culture. Like Menachim, who delivered these amazing speeches in 1950s that spoke to the people.

Galit Eilat: What about the location? You chose the old Olympic stadium…

Yael Bartana: I knew very soon after starting the piece that this would be the location where he would deliver the speech. Because it’s abandoned, because speeches in stadiums are connected with Nazi propaganda films. The stadium and the camp are two architectural elements of Nazi Germany. That’s also why Wall and Tower references them. But clearly, it’s absolutely not suggesting a perfect, powerful fascist architecture; the stadium is abandoned and in ruins. So it has this ghostly feeling — of something that was there but is gone.

Charles Esche: …and Wall and Tower feels like a continuation of the story.

Yael Bartana: Yes, for sure. Wall and Tower is really about creating historical mirrors by way of repetition. It’s about displacements, about how the same act takes on different meanings when moved to another geographical area. It is also about nostalgia, not in the sense of a passive emotion, but as a way to enable an alternative way of thinking. What does it mean to build a Kibbutz in the area of the former Warsaw Ghetto today? The new Kibbutz was erected on the site where the future Jewish Museum of Warsaw will be built. But for me, this project is not about memory and creating a museum out of something, but about establishing a relationship to contemporary Israeli politics. Jews coming to Poland today would not constitute a Diaspora anymore, but would be closely linked to a specific nation-state, to the militaristic rhetoric and politics of Israel. That’s why the “The Jewish Renaissance Movement” that I founded in Poland even has a flag combining the Polish eagle and the Star of David. The reverse perspective on history, which the film is set to explore, positions it on a new, subversive level. The film juxtaposes reality and fiction, encouraging the viewer to reexamine constructed ideas of historical events. For me, it has actually become more and more interesting to create proposals rather than counter existing narratives. That is, to create proposals for solutions or to create situations that make people think differently.

Charles Esche: There are many powerful moments in both films, including the description of the quilt in the beginning of Mary Koszmary and this moment when Sierakowski says “Citizens, Jews, People,” and then you pan across these empty terraces, which is such a powerful image of absence and the open wound of Europe.

Galit Eilat: Wound of what?

Charles Esche: The absence of the Jewish community from the heart of Europe.

Galit Eilat: Why don’t we stop talking about it like that? We’re not talking about the absence of Jews — we’re talking about the absence of three million people.

Charles Esche: But three million people who represented some sense of community. It wasn’t that there were three million, and then there were forty million left. It was that the community was destroyed.

Galit Eilat: This is something that I think that the film deals with — the symbolic, and how we are attached to feelings that accompany our dealings with the state, ideology, religion. What makes you different from others? Because if we push away all ideology that contains religion and the state and other things, we can just say that three million out of many more millions died in Poland during the Second World War.

Yael Bartana: But they saw themselves as different, and so did the Nazis.

Galit Eilat: Together with other groups, like the Roma.

Yael Bartana: They wanted to make a homogenous society, to give a clear direction to it. You can’t say they just killed people without remembering that.

Galit Eilat: But the point is, saying “we are missing our Jewish community in Europe” sounds very awkward to me. Why only the Jewish community, and not many other communities that are gone, or were reduced, during the Second World War?

Charles Esche: Perhaps, but remember that with the loss of the Jews, the Russians and the Germans, the whole idea of Poland as a cosmopolitan culture was lost. It became 98% Polish, which it never had been in the past.

Galit Eilat: But this is also the idea of Israel: to be ethnically clean. The existence of Israel is also predicated on turning cosmopolitan societies into homogenous societies. If you say, “We need more Jews in Europe,” it means that Jews are different from others, and I don’t like that idea. Judaism is another kind of ideology, like Zionism, Communism or Christianity or… it’s the same. In this sense, I don’t like that kind of a vision.

Charles Esche: But the idea of a cosmopolitan culture, the idea of mixture, the idea of immigration, are based on some measures of difference. I am saying that this mixing is at the heart of this Asian peninsula we call Europe. Homogeneity doesn’t belong in Europe; it’s a consequence of the great wars of the 20th century.

Galit Eilat: It’s not about a choice between homogeneity or difference. You can have difference that is not in terms of religion, the state or ideology.

Yael Bartana: Can I suggest something? Let’s read this project of asking the Jews to go from Israel to Poland as a new proposal, a possibility for some movement, a new shift in life. An event in history. Something else that could happen. Just an idea. Just a fictional idea. The Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland has a manifesto. You don’t have to be a Jew. If you want to join, you can: it’s a proposal, a new movement. Just like Zionism, which had this idea of finding the solution for the Jewish problem in Europe by moving everyone to Palestine, without considering what was (already) there… So, this is a proposal. I’m playing the same game.

Charles Esche: Yeah, exactly! It’s Neualtland ! (laughs)

Galit Eilat: (laughs) “Neualtland”… You know, in Tel Aviv, there is a question about the name “Tel Aviv”— that is, what is “Tel Aviv”?…

Yael Bartana: It’s the same: it’s Altneuland.—

Charles Esche: — and now: Neualtland.

Yael Bartana: Neualtland!

Galit Eilat: Yes, the competition is not with Avodah, it’s with Herzl. (laughs) Who can write it?

The Movement of Jewish Shadows. Marek Beylin

When Yael Bartana called into existence the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland, she automatically lost absolute control over it. Everyone who feels called out to the blackboard by her work can, and actually should, put in their two pennyworth about how they imagine the movement’s role, so let me make a few remarks myself. In Mary Koszmary (Nightmare), a Pole’s appeal for Jews to return to Poland is an appeal for the return of Polishness. A Polishness that keeps confronting itself with its own ‘others’, with the Polish Jews. A Polishness forced to constantly ask itself about what it is and to use the answer to rediscover its own diversity and colourfulness. We are grey and homogeneous, and therefore sad and frightened, the Leader says in Mary Koszmary. Our trespasses against you have been all the heavier a burden since we have repressed them, and are being amplified by your absence, because our fear of Jews is actually a fear of ourselves, of looking boldly into our own unclean conscience. So come here to release the constrained Polishness so that, through your presence, we can look into ourselves. Bring us our joy and colours, bring us the diverse, multicultural Poland — that’s how the Leader’s message could be interpreted.

And so they came. In Wieża i mur (Wall and Tower), they are here, building a kibbutz on the site of the former Warsaw ghetto, where the Holocaust took place, near the Umschlagplatz, from where the Germans sent several hundred thousands of Jews to the ovens. If I understand well, these newly arrived Jews are supposed to replace those murdered by the Germans and those killed, turned in and robbed on the ‘fringes of the Holocaust’, to use a term coined by a Polish historian, by their Polish neighbours.

But paying heed to Israeli experiences that advise caution, and in accordance with a spirit of time that advises minorities to guard themselves against majorities, the kibbutzniks surround the kibbutz with a wall and erect a tall watchtower inside. Seen from outside, the wall and tower are symbols of mistrust and strangeness. But from the perspective of the kibbutz itself, the wall and gate are not only an expression of vigilant uncertainty, but also an invitation: come and see us in our kibbutz normality, even if the normality were to be hard to understand for you. We have come here not to be strangers in a strange land, but to become your strangers who, by disturbing, challenge you to accept the rule that, as the German philosopher Bernhard Waldenfels puts it, ‘human beings will never be completely at home in the world, and … nobody can claim to be the master of his own home’ (1).

This communication claim made by the kibbutzniks and the Leader inviting them has been neither fulfilled nor even acknowledged. Seen from the perspective of the street, the kibbutz gate is a part of the wall blocking from view an unfamiliar, and thus frightening, reality, rather than inviting one to enter. The same gate, seen from inside the kibbutz, becomes increasingly a sign of illusion and disillusionment that accompany a communication failure.

What is missing between the Poles and the kibbutzniks is a liaison, a connecting factor: the Jews murdered in the Holocaust. But their shadows, ever more intensely present in Poland and, at the same time, persistently relegated into oblivion by the majority, are there. If the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland is to take root here, it should integrate these Jewish shadows. But what exactly would that be supposed to mean?

Let us accept after numerous philosophers that at the beginning of social life is difference rather than unity. This is a friendlier faith, one that protects from the temptation of singularity and ‘completeness’ (2). It stifles aggression and, in extreme cases, also the genocidal tendencies displayed by ethnic, religious or cultural majorities. Such a readiness to violence is born when minorities remind majorities with their existence of the ‘small gap which lies between their condition as majorities and the horizon of an unsullied national whole, a pure and untainted national ethnos’, as Arjun Appadurai argues (3).

Frequent in the world and present also in Poland, aggression against minorities, or rather against constructed fictions about them, such as that they will dominate the majority or that under their ‘normal’ surface hides a treacherous nature, stems from the majority’s futile efforts to build its own singularity: the singularity of Poles in Poland, or of men or heterosexuals in society. To snatch and free Poles from their sense of completeness is the Movement’s fundamental task. The Jewish shadows are wandering shadows, lacking any mundane haven in their lifetime. These shadows are our Other. For Waldenfels, at the beginning is not humanity in everyone and not otherness in oneself, but humanity in the Other. ‘The other is the first human being, not I’, he quotes Husserl (4).

These Jewish shadows are our humanity. But for them to change us, we must avoid familiarising them, avoid reducing them to our own standards and identities. They would then become merely exotic, so they have to remain as they are: strange, and therefore disturbing. Then perhaps we will become able to respond to the challenge that their presence faces us with, and will be given a chance, while talking about ourselves, to notice the cracks in otherness also in us. Because they are present in everyone and only need to be acknowledged. And if we accept that otherness is not a horrifying aspect of the outside world that needs to be co-opted and reduced to familiarity, but is also a part of ourselves, and one worth particular attention, then we will be able to walk confidently through the kibbutz gate, and the wall and tower will become unnecessary. By virtue of the Jewish shadows.

(1) B. Waldenfels, The Question of the Other, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2007, p. 4.

(2) Arjun Appadurai uses the term in Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

(3) Ibid., p. 8.

(4) Waldenfels.

New Europe’s nightmare. Nina Möntmann

In Yael Bartana’s Polish video trilogy, aside from the politically symbolic aspects it contains, the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP) that she had initiated, announces its manifesto on a new experimental societal form.

This manifesto depicts a notion outlining a concrete political scope for action relating to this project. This is not a Zionist movement that yearns for the Palestine. It yearns for Poland, inside the fortress of Europe. It has no need for any territory marked by borders because it intends simply to plug in. Neither mono-ethnic nor mono-religious, it is international and open to all refugees and outcasts. Horizontally interconnected like a network, it needs no central leader. It is a political experiment

Amidst the thoroughly capitalistic countries of the former Eastern Europe, this movement offers a model that will put the Western double-standards democratic concept to a test. The rhetoric of the new post-communist Europe speaks of the promise of openness and inclusivity. In reality though, the individual nations pursue elaborate practices of separation embossed with xenophobia. The JRMiP project is like a nightmare for this Europe. All those who do not pass through the filter are welcome here, whether they be Jews, who merely because of their physical presence stir up feelings of historical guilt, or those who remain stranded on Lampedusa, or those sweltering inside crammed refugee camps of France or Germany. All are welcome who have been expelled from Europe, whose families had been annihilated, or who are seen today as being a threat to industrial prosperity and the „Western culture“. Whether they embody the ‘Multitude’ as proclaimed by Negri and Hardt, or the network of politically inclined youth, their potential lies in the All, which when measured against current standards, has nothing to lose: and so it revolts.

The revolutions in the Middle East — the Arab Spring — have also been triggered by the politicisation of young people without perspectives. And here too, one can again see the reluctant reactions of the West, see how Western democracy functions applying its binary (dividing the world into two) way of thinking when it comes to the principles of global capitalism. Hence, its tolerance for the support offered to brutal dictators who hold their people in check and throw any potential refugees who would wish to get to Europe into some dark and remote prisons — naturally of course also with the aim of remaining in charge of their oil reserves. And so, in the end, the West needs not to worry about the deprived and oppressed people in these countries, it does not have to share with them the oil and is offered free access to these resources in the Middle East. These undesirable migrants too will be welcomed by the JRMiP.

In theory, the possible democratisation of the people of the Middle East that might be forced by the revolutions could tip the concept of Western democracy, or at least, it will put it to a test. But this is based on the assumption that the despotic rulers together with their thugs, their entourage and their beneficiaries will leave and that the newly politicised youth and their yet unformed organisations will be left to themselves. It also assumes that the people who will now be given the right to vote, and those candidates who will be standing up for election hold a broad enlightened and non-ideological view of nation, such that does not regard religion or a particular culture or a common history as its binding factor.

The JRMiP arrives to all this with its small societal experiment. It turns its back on Israel’s apartheid politics, but also on all other right-wing politicians, groups and theorists with an essentialist notion of culture. As Zeev Sternhell put it ‘If Nicolas Sarkozy, the political figure, Alain Finkielkraut, the intellectual, the Islamists, the nationalist religious Jews of Israel, and the neoconservatives and their evangelical allies in the United States are all waging, in spite of appearances, the same fight, it’s because they all assert, with Herder, that every person, every historical community has its own specific and inimitable “culture”, and that this is what must come first.’

That society which the JRMiP is calling forth is as ethical as an ethnic nation State. It is inclusive in the way it is organised and international in its thinking. Against the major revolutionary changes taking place in the Middle East, the JRMiP offers a flexible platform that will put Europe to a test – as a zone for a unique ethical activity. This is not about overturning a leader and dismantling a state system, but should, as envisaged by the plug-in principle, settle down like a guest next to its host. It will be an unwanted guest who will put its host on edge, forcing him into a debate with own historical guilt, confronting him with ghosts and noting whether he is prepared to face all that. The JRMiP is a complex and open political experiment, armed with a democratic-activist manifesto.

Zeev Sternhell, ‘From a Nation of Citizens to a Cultural Nation. Anti-Enlightenment Thinkers of the World’, in Le Monde diplomatique, 14.1. 2011, p. 3., translated into English by Mark K. Jensen.

A Polish State in The Land of Israel. Yuval Kremnitzer

“There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk around the world till we come back to the same place”.

G. K Chesterton

For thousands of years the imagination of the Jewish people in the diaspora was captivated by a simple trajectory: the exile from the land of Israel, the punishment of exile in the diaspora, and the anticipated return to the Promised Land, upon the coming of the Messiah. Or so we are told. The Zionist project had turned that eschatological dream to a political program. Though that project was an incredible success in many ways, establishing a Jewish state in fact in the land of Israel, it has done so not only at the price of bringing a disaster upon the people already inhabiting that land, and also at the price of turning the land itself into an exile of sorts. Though that state has now been a reality for more than sixty years, in the political imagination of Israelis from all sides of the political map it is clear we have not yet arrived in the Promised Land. Some respond to this insistent longing by settling in territories beyond the recognised borders of Israel, while others have come to believe that the true home of the Jew is the diaspora itself, that Jews are somehow only at home away from home.

The political project of identifying the home of the Jewish nation in exile brings to mind a series of possible returns. To Poland, to Germany, to Spain, and, why not, perhaps the most attractive option these days, to Egypt. The Jewish diaspora has had a sometimes flourishing, often troubled relationship with many of its host surroundings. But Poland is more than yet another temporary home for exiled Jewish communities. It has a stronger, unique claim to being the home of the Jewish people, a home, however, they might never have left.

Engaging the task of imagining a Jewish state in Poland calls for an act of cultural translation. Not only because it would be impolite and imprudent to create a new community without sharing the particular imagination with which one enters this union, but also because, in imagining this community as new, one must first be familiar with the old, especially, as will shortly become clear, one can call into question the novelty of the enterprise. One could very well argue that a Jewish-Polish state already exists: the Polish state in the land of Israel, namely, the state of Israel.

Israelis approach the subject of Poland through their cultural perception of “Polishness”. The very existence of the term suggests that “Poland” is filtered through more than the usual stereotypical filter that allows us access to anything unfamiliar. But in fact it comes to stand for something that is all too familiar.

In Israel “Polishness”, a rich source of jokes and humor, is associated with the figure of the overprotective “Polish mother”, with a passive-aggressive economy of guilt, and with the figure of the neurotic and hypochondriac effeminate man. The list could go on, but by now the point should be clear: replace the word “Polish” with the word “Jewish” and you’ll have most of of the building blocks for humor and jokes that comprise the stereotypical image of the Jew outside Israel, at least in Europe and the U. S. (Most but not all — the rich theme of greed associated so often in jokes with the figure of the Jew was transposed instead onto the figure of another Eastern European, “the Romanian” ).

How and why “Polishness” came to stand, in the land of Israel, for what outside of it is known as “Jewishness”, is not the concern of this short essay, nor are many of its otherwise interesting implications, such as how the figure of the “Polish/Jewish mother”, a universal figure of a maternal super-ego, secretly enjoying its offspring’s unavoidable failure to satisfy her wishes, has become codified as particularly “Jewish”, or in the Israeli case, “Polish”, or the identification of “Jewishness” with a particular Eastern European image of the Jew, precisely the one that also captivated the gaze of the Nazis, namely, that of the Ostjude.

It is perhaps easy to see why such a stand-in figure for the Jew had to be created in the Jewish state, seeking to replace the diasporic, homeless effeminate man with a new man, strong, masculine and grounded. However, as we shall see, the creation of “the Pole” as a stand in for “the Jew” did not result in a clear-cut break with this figure, far from it. In creating the figure of “Polishness”, the exile, and the exile Jew, were not simply negated or externalised. Indeed, by creating this figure, “Jewishness” has instead been internalised and universalised.

To see the full scope of this process would require many more words, and a lot more evidence. As our focus here is political imagination, we should restrict ourselves to a few short comments as to the implications of this encapsulation of “Jewishness” within “Polishness” in the popular culture of Israel, on the politics of Israel, and its possible ramifications for the Jewish state in Poland.

In Israel, attitudes identified with “Polishness” are to be found at the very core of politics. Perhaps the finest example for this is Golda Meir’s infamous saying, according to which “we will never forgive the Palestinians for what they made us do to them”. This statement, making the victims of violence bear the guilt for their own misfortune, reads, to the Israeli eye, as “Polishness” turned state policy, as does the security policy of Levy Eshkol, Meir’s predecessor as prime minister of Israel, that he adequately named, in Yiddish, “Shimshon der nebechdiker”, “Samson the weakling”, suggesting Israel’s might lies in its weakness, and its turn to violence only a desperate last resort of self-defense. For years, Israeli violence had to be codified in passive-aggressive language. The Jewish state could not be directly aggressive, but rather had to color its own aggression as a terrible burden it unwillingly bears, for which the objects of that aggression are to be held responsible. That these days we are witnessing in Israel, for the first time publicly, a call for more direct, unapologetic aggression, should therefore not be taken lightly. It signals a profound shift in the national self image, perhaps one that is finally willing to part ways with its own “Polishness”.

“Polishness” is also understood to be an attitude preoccupied with what others might think, always anxious about possible embarrassment, of an indecent exposure, letting something that should be kept hidden slip and enter the field of vision of an outsider. In recent years, the moral debate in the media, if in fact it can be called that, with regard to the morality of Israel’s actions against the Palestinians, was predominantly based on a “What will the (Gentile) neighbors say?” rhetoric. Israel’s violent actions against the Palestinians are rarely measured by a public moral consciousness, asking, “Is this right” or “Is this who we want to be?” Rather, it is framed under the question of the external perception of those actions — “Is this how we want to be perceived” — as if in themselves these raise no moral issue, but are a cause of embarrassment, due to the external, misguided yet somehow all-important gaze of the outsider.

The central role this gaze plays in Israeli society can be exemplified through the joke about the (Eastern European, shtetl-dwelling, Polish) Jew riding the train from Minsk to Gdańsk. Finding himself alone in the train car, the Jew makes himself comfortable, loosening his belt, taking off his shoes, and so on. Just as the train is about to leave the station a properly dressed Polish gentleman enters the car. The Jew, embarrassed, rapidly collects himself, fastening his belt, putting on his shoes back on, and so on. After an hour of awkward silence, the Polish gentleman pulls out of his jacket a siddur, the Jewish prayer book, and starts praying. The Jew from the shtetl looks at him and says, “Why didn’t you say so?”, and immediately starts loosening his belt, taking off his shoes, etc.

The lesson of the joke is twofold: two Jews are never strangers, even when from opposite classes, and this (over)familiarity is guaranteed by the absence of a real stranger, namely, a Gentile. It is not so much the public/private divide that constitutes the space of familiarity here, but rather the presence, or the absence of the Gentile. (The history of the term pharhesia, borrowed from the Greek and coming to stand for a kind of overexposed publicity in contemporary Hebrew, leads to a similar conclusion: pharhesia is not so much in public, but in the presence of, or exposed to the gaze of, the outsider/Gentile. )

On the face of it, this is precisely the dimension of Jewish identity that was to be left behind, in exile, with the establishment of a sovereign Jewish state in the land of Israel. Sovereign in their own land, the Jews should no longer be subject to the gaze of the Gentile. But this is precisely where we come to see that the negation of exile and the exile Jew was a dialectical negation in the Hegelian sense, preserving and raising to a higher domain as it negates.

Take the figure of the stereotypical Israeli “sabre” (tzabar) – thorns on the outside, sweet on the inside. The Israeli prototypical identity seemingly replaces the passive-aggressive with the aggressive-aggressive; worry and embarrassment in face of the other’s gaze is replaced with a straightforward and direct chutzpa, shameless and uninhibited, and the status of the eternal wandering Jew, nowhere at home, is replaced by the grounded Jew, at home in his country and (infamously) behaving everywhere as if it were his home. But this clear cut opposition is misleading. In fact, the gaze of the other as a constant threat of exposure is not merely negated, but rather sublated and universalised. Perhaps one effective way of demonstrating this is by drawing attention to everyday practices of greeting. In many cultures there is an implicit yet highly codified manner of how one is to greet a stranger, an acquaintance, and so on. A handshake, a kiss, two kisses, etc. In a sense, one is granted (initial) access to a society upon learning these implicit entrance codes, sparing oneself the awkwardness of being a complete stranger, a newcomer. Interestingly, there is no such code in Israeli culture. One should beware of reading this absence of codification as something merely lacking. Instead, this absence should be read positively, as inscribing a certain awkwardness into the moment of encounter. What seems to be an (overly) familiar code of behavior (people in Israel often address each other as ‘brother’ and ‘sister’), a final release from the gaze of the ‘big other’, the Gentile, is in fact the universalisation of this gaze: every encounter with the other, even one’s friend, is initiated with a brief moment of uncertainty as to the appropriate way to greet her, rendering the judgmental, external gaze ubiquitous. The same holds for the lack of social and linguistic distinctions as to how one is to address members of different social strata. No university professor is addressed as professor, but rather by their first names, and the use of ‘ma’m’ or ‘sir’ is interestingly usually a sign of hostility, rather than politeness, as if the addition of the formal, symbolic distance is a sign of the foreignness, and therefore implied animosity, of the one addressed. Finally, the Hebrew word for citizen, ‘Ezrah’, comprises the Hebrew word for brother with the word for stranger in it. This should not be taken to mean that a citizen is a stranger who is also one’s brother, but rather that every brother contains within him the stranger. In conceiving itself more and more as a community of brothers, based on kinship, and excluding the members of society that do not fit in this family tree, Israel is disavowing its sublation (internalisation and universalisation) of “Polishness”, imagining it instead as a clear-cut negation.

“They were friends like brothers, that is, having no other choice.” — Assaf Schur.

If all of these are markers of the Polish state in the land of Israel, as I suggest, what is the substance of a Jewish state in Poland? Can it be more than yet another reversed mirror-image of the same? Should it strive to be that? Can one harness the great revolutionary energies that characterized the Zionist project in its beginnings and yet avoid the tragic destiny that seems to have befallen it? As we come to realise that new beginnings do not entail a complete break with the past, what can the Jewish state in Poland learn from its older sister, the Polish state in Israel?

Though one can hardly recommend a Golda Meir-like attitude to state aggression, perhaps in the Israeli sublation or negation of “Polishness” there is something the Jewish state in Poland should adopt. Beyond the veil of phantasy, no community can be rid of the image of the stranger. Rather than imagining a community without any barriers between its members, perhaps a universalisation of that strangeness, the presence of the stranger within every brother, should be taken as a positive model for imitation. If Israeli citizenship seems to be coming apart, it is not because this attitude is untenable, but rather because it has been disavowed. Instead of affirming the universal strangeness of the fellow citizen, Israel has insisted on creating “real” strangers, to exclude from the “real” community of forced brothers. May that be a lesson for our younger sister: one’s brother is, before anything else, someone you didn’t choose to share your life with. And if that is so, perhaps it is less urgent to distinguish between one’s brothers and one’s foes.

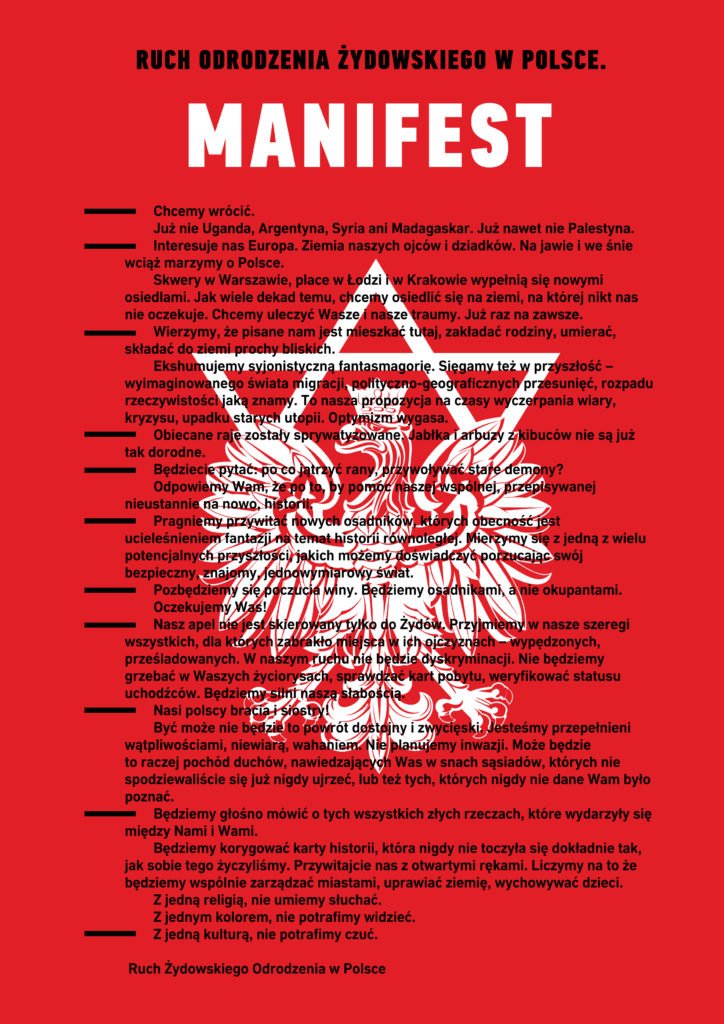

The Jewish Renaissance Movement In Poland: A Manifesto

We want to return! Not to Uganda, not to Argentina or to Madagascar, not even to Palestine. It is Poland that we long for, the land of our fathers and forefathers. In real-life and in our dreams we continue to have Poland on our minds.

We want to see the squares in Warsaw, Łódź and Kraków filled with new settlements. Next to the cemeteries we will build schools and clinics. We will plant trees and build new roads and bridges.

We wish to heal our mutual trauma once and for all. We believe that we are fated to live here, to raise families here, die and bury the remains of our dead here.

We are revivifying the early Zionist phantasmagoria. We reach back to the past — to the world of migration, political and geographical displacement, to the disintegration of reality as we knew it – in order to shape a new future.

This is the response we propose for these times of crisis, when faith has been exhausted and old utopias have failed. Optimism is dying out. The promised paradise has been privatized. The Kibbutz apples and watermelons are no longer as ripe.

We welcome new settlers whose presence shall be the embodiment of our desire for another history. We shall face many potential futures as we leave behind our safe, familiar, and one-dimensional world.

We direct our appeal not only to Jews. We accept into our ranks all those for whom there is no place in their homelands — the expelled and the persecuted. There will be no discrimination in our movement. We shall not ask about your life stories, check your residence cards or question your refugee status. We shall be strong in our weakness.

Our Polish brothers and sisters! We plan no invasion. Rather we shall arrive like a procession of the ghosts of your old neighbours, the ones haunting you in your dreams, the neighbours you have never had a chance to meet. And we shall speak out about all the evil things that have happened between us.

We long to write new pages into a history that never quite took the course we wanted. We count on being able to govern our cities, work the land, and bring up our children in peace and together with you. Welcome us with open arms, as we will welcome you!

With one religion, we cannot listen.

With one color, we cannot see.

With one culture, we cannot feel.

Without you we can’t even remember.

Join us, and Europe will be stunned!

Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland

Yael Bartana. Works

Zamach (Assassination)

Yael Bartana, Zamach (Assassination), 2011 RED transfered to HD, Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv

The film was commissioned by Artangel, Outset Contemporary Art Fund, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, The Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture and Zachęta National Gallery of Art

In association with Annet Gelink Gallery, Sommer Contemporary Art, Ikon Gallery, Netherlands Film Fund, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art and Artis

Produced by My-i Productions in association with Artangel.

Mary Koszmary (Nightmares)

Yael Bartana, Mary Koszmary (Nightmares), 2007, Super 16mm transfered to Blu-Ray, Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower)

Yael Bartana, Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower), 2009, RED transfered to HD,·Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv