‘Once and for All’: The Story of the Creation and Architecture of the Polish Pavilion in Venice

Works by Polish artists have been shown at the Venice Biennale since the late nineteenth century, and since the early 1930s they have been presented in a separate national pavilion, which has yet to attract much interest from scholars.[1] The decision to build a permanent pavilion, which expressed Poland’s aspirations for equal partnership in the international community, was a key moment in the history of the nation’s presence at the Biennale. The building owes its creation to the coinciding interests of the Polish government and the exhibition organisers.

1. Modern-day plan of the Giardini grounds, with the Polish Pavilion marked as no. 13, from: Marco Mulazzani, Guide to the Pavilions of the Venice Biennale Since 1887, trans. Richard Sadleir, Milano: Electa, 2022 (1st ed. 1988), cover flap

Poland as a ‘tenant’

Poles have been displaying their work at the Biennale since 1897 – initially in the Austrian, Russian, or international sections, organised in the main pavilion (ill. 1, no. 1 on the map), the only Biennale building at the time. The first separate national pavilion, built for Belgium (no. 2 on the map), not far from the main exhibition building, with a composite Art Nouveau aesthetic, opened in 1907. After that came the Hungarian pavilion (no. 3 on the map), built for the exhibition in 1909 – in the national style, joining elements of the vernacular with prominent decor.[2] Beforehand, however, in 1905, Hungarian artists had presented their works in a separate hall of the main pavilion. Thus, we can see that the organiser (the municipality of Venice) had permitted nations that did not have their own state to be represented. In 1912, art historian Władysław Kozicki stated that ‘the best way out of this situation would be if one of our tycoons were to build a permanent pavilion for Polish art in Venice’,[3] which was not an entirely utopian idea. Acquiring a separate (sometimes permanent) exhibition space was possible if a nation or institution had plenty of determination and organisational skills. In 1910, Polish works were shown alongside Czech artists in the central pavilion,[4] and in 1914, the ‘Sztuka’ Society of Polish Artists had a separate display – the first independent Polish show at the Biennale.[5]

In 1920 the Polish exhibition was presented in the German pavilion (ill. 2, no. 4), which was abandoned and never fully paid off (it was an investment financed by the Biennale).[6] Originally intended for Bavarian artists, the building was designed by Daniele Donghi, Venice’s municipal engineer, in a simplified Neoclassicist style.[7] The commissioner of the exhibition was a painter named Władysław Jarocki; in June of that year, he told the Ministry of Art and Culture:

… I have talked to the Venice city council and Board of the International Art Exhibition in Giardini pubblici about purchasing the pavilion in which I assembled an exhibition of Polish art at the Ministry’s behest.… The Venice City Council and Exhibition Board are prepared to sell the Polish Government this pavilion for the sum of 150,000 lira.… The international art exhibition in Venice has gained world renown and Poland’s participation is highly desirable; owning our own pavilion would give us the opportunity to set the exhibition program many years in advance ….[8]

Despite the relatively low price and the support of Minister Jan Heurich,[9] the pavilion was not ultimately purchased, contrary to the information in Kurier Polski.[10] Mieczysław Treter thought the transaction fell through because of the bureaucrats’ ‘criminal neglect, incompetence, and procrastination’.[11]

In the following years, the Polish authorities’ interest in the Venice exhibition decidedly waned,[12] while arts commentators increasingly pointed out the Biennale’s major importance on the international scene – Zofia Norblin-Chrzanowska called it the ‘League of Nations for the arts’.[13] The next appearance of the official representation of Polish artists in this ‘international tournament’,[14] again organised by ‘Sztuka’ Society, occurred in 1926. Once more, the Poles were assigned one room in the main pavilion. In the autumn of that year, the Society for Dissemination of Polish Art Abroad (TOSSPO) was brought to life under the management of Treter, controlled by the Department of Foreign Affairs.[15] The society lobbied with the authorities for the construction of a Polish pavilion in Venice. By 1926, the Biennale organisers had agreed to ‘highly amenable conditions’ and a proposal for the new building’s location,[16] but these plans fell through. At this time, the pressure the Biennale exerted on Poland to build their own exhibition site was markedly increased. The organisers refused both TOSSPO and ‘Sztuka’ Society a space in the central pavilion

In January 1930, Antonio Maraini, secretary general of the Biennale, and a sculptor and fascist politician, laid out ‘detailed conditions and proposals’ to the TOSSPO for the construction of a Polish pavilion.[17] This time, the Polish government accepted the offer. Wacław Husarski, the commissioner of the modest Polish exhibition during the Biennale of 1930,[18] eexpressed satisfaction in Tygodnik Ilustrowany that Poland’s period as a ‘tenant’ was now over, which he saw as ‘compromising our dignity’. Husarski stated that the exhibition directors had developed ‘a project of six [actually five – W.G.] new pavilions … one of which is designated for Poland’. The construction costs were meant to stay within 200,000 lira (around 100,000 zloty).[19] The Polish decision-makers did not have to ponder what architectural idiom to choose for the Venice pavilion, which became the property of Poland in 1932, as the Biennale determined the look of the building

Exhibition pavilions in the 1920s

When preparations were underway for building the Polish pavilion, apart from the aforementioned national pavilions there were already buildings for Great Britain, France, Holland (originally Sweden), Russia, Spain, Czechoslovakia and the United States; Denmark, like Poland, gained its own venue in 1932. The designs of most of the pavilions (excepting the German and French) were prepared by architects representing the countries in question. The commissioners and designers consciously chose the language of the buildings’ architecture, giving them national traits. Depending on the needs and the ways of creating a visual identity in various countries, they stressed roots in tradition, used a historical look, or stressed modernism. Participating in the world’s art scene in the 1920s, Poland also skillfully used architecture as a means of cultural diplomacy to shape the direction of the modern state, as in the presentation at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925.[20] A major contributor to that Polish success was the designer of the art déco pavilion, Józef Czajkowski. The modern architecture of the pavilions was also used in domestic propaganda, e.g., during the National General Exhibition in Poznań in 1929, where, alongside buildings in the national style, there were structures in a simplified, functionalist vein. Most of the pavilions at international and domestic exhibitions were temporary, sometimes preserved in situ or transported elsewhere (the ‘Stahlkirche’ from the International Press Exhibition in Koln, designed by Otto Bartning, 1928) or even reconstructed many years later (the German pavilion from the world exhibition in Barcelona, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, 1929). The pavilions of the Venice Biennale, though they might have undergone crucial transformations to suit the changing needs of clients and the tastes of the epoch, were built to be permanent structures.

Brenno Del Giudice

The Polish Pavilion is part of a complex of five exhibition venues designed in 1930 by Brenno Del Giudice (1888–1957), who graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice in 1908.[21] He was the first architect admitted to the group of exhibition participants in Venice’s Ca’ Pesaro, where works by avant-garde artists were shown – he took part in 1910, 1919 and 1925.[22] Since at least the end of the 1910s, he had worked with painter Guido Cadorin – a school friend and his brother-in-law. They jointly exhibited in the National Exhibition of Sacred Art in Venice in 1920, showing designs for temples and their decor. Del Giudice and Cadorin joined three other artists to form the Gruppo per l’Architettura e l’Arredamento [Group for Architecture and Furnishing], offering complete church and furnishing designs, probably in response to the need to reconstruct sacred buildings after World War I.[23] We do not know, however, any of the works of this ephemeral collective. Del Giudice was particularly interested in sacred architecture and created many church designs in the 1920s. He and Cadorin won a competition for apse mosaics in the San Giusto church in Trieste. They also took first prize in a competition for the cathedral in La Specia, though their monumental Renaissance-inspired vision was never carried out.

The idea of uniting three arts (painting, sculpture, architecture) and the harmonious collaboration of artists of various specialties was dear to Del Giudice. Apart from the above-named initiative, we can find this as well in the creation of an arts ‘brigade’, whose members (among them Cadorin and Del Giudice) turned to politician and poet Gabriele D’Annunzio to request his patronage of the undertaking.[24]

In his early designs, such as Villa Papadopoli in Vittorio Veneto (1919) and the Pharmacist’s House in Lido (1926–1927, ill. 3), Del Giudice was also inspired by traditional Venetian architecture.[25] He did not emulate historical solutions, as one scholar of his work, Giovanni Bianchi, has claimed; he interpreted them in the light of modern Art Nouveau tendencies, in accordance with the picturesque Barocchetto style that was all the rage in Italy. In his designs for the Philip and Jacob Church in Candelù (1921–1924) and the Christ our Lord temple on Sant’Erasmo island in Venice (1926), he drew from the rugged simplicity of Romanesque solutions and the local traditions of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, joining it with liberty (Art Nouveau) and art déco styles.[26]

3. Brenno Del Giudice, Pharmacy House, Lido, 1926–1927, from: Marcello Piacentini, Architettura d’oggi, Paolo Cremonese, Roma 1930, unpaginated.

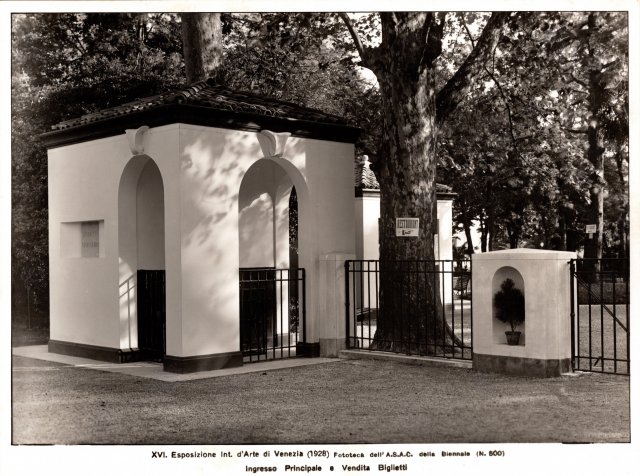

4. Brenno Del Giudice, Biennale entrance pavilion, 1926, ASAC

The New Face of the Biennale

From the mid 1990s to the outbreak of World War II, Del Giudice was, alongside Diulio Torres, the Biennale’s main architect. Vittorio Pajusco’s research shows that these two young lecturers of Venice’s freshly created Architecture Academy (presently: Università Iuav di Venezia) were key advisers to the Biennale’s organisers in modernising the exhibition infrastructure.[27] The sprawling terrain of the park where the exhibitions are held afforded the designers highly attractive conditions for new structures, as compared to the historical, densely packed urban fabric of Venice, and the Biennale encouraged modern formal solutions.

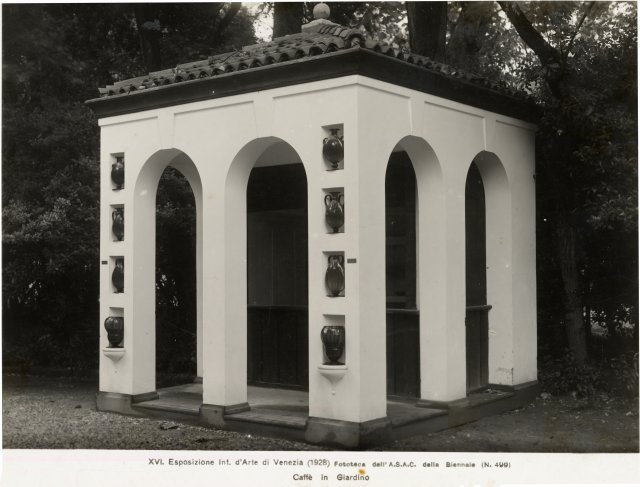

In 1925, Del Giudice received a commission to make the poster for the fifteenth edition of the Biennale, held the following year.[28] He was also behind the kiosks flanking the many entrances to the Biennale grounds and the ticket booth – small cubes punctuated by arcades, built in 1926 (ill. 4). In the single-floor entry pavilions he used large, chunky keystones for the arcades, contrasting with the simplified, pictorial look of the elevation. That same year, he also designed a kiosk that held a bar (ill. 5). On the outer side of the pillars on one of the walls, which opened up on all four sides with arcades, he placed niches decorated with glass vases. In his first Biennale projects, which have not survived, Del Giudice discarded the old language of eclecticism and used modernist forms; this was greeted with enthusiasm, as consistent with the needs and views on architecture of the day.[29]

5. Brenno Del Giudice, coffee kiosk in Giardini, 1926, ASAC

Antonio Maraini took over as secretary general of the Biennale in 1928, a watershed moment in the history of the exhibition.[30] He strove to make the institution independent from the city authorities; this occurred in early 1930 and was approved by the Italian government, which wanted to make freer use of the Biennale as a propaganda tool. Before the exhibition in 1928, the decision was made to rebuild the central pavilion. Del Giudice was asked to design a new café in this building and an adjoining terrace (ill. 6, no longer existing). The designer stressed the rhythm and regularity of the architecture of these elegant spaces, again using a simplified composition and a modernist synthesis of forms. Photographs of the café were often reproduced in the press, and the interiors garnered very flattering reviews.[31]

6. Brenno Del Giudice, coffee house in the main Biennale pavilion, 1928, photo: Giacomelli, ASAC

The architecture of the Polish Pavilion

As we have recalled, from the mid 1920s the Biennale council was reluctant to present national exhibitions in the central pavilion, encouraging participants to build their own pavilions in the Giardini. With every passing year the available grounds decreased, so the decision was made to use the Sant’Elena Island, adjacent to the park from the east and separated by a canal, to increase the exhibition space. Del Giudice was then commissioned to make a building to house five pavilions.

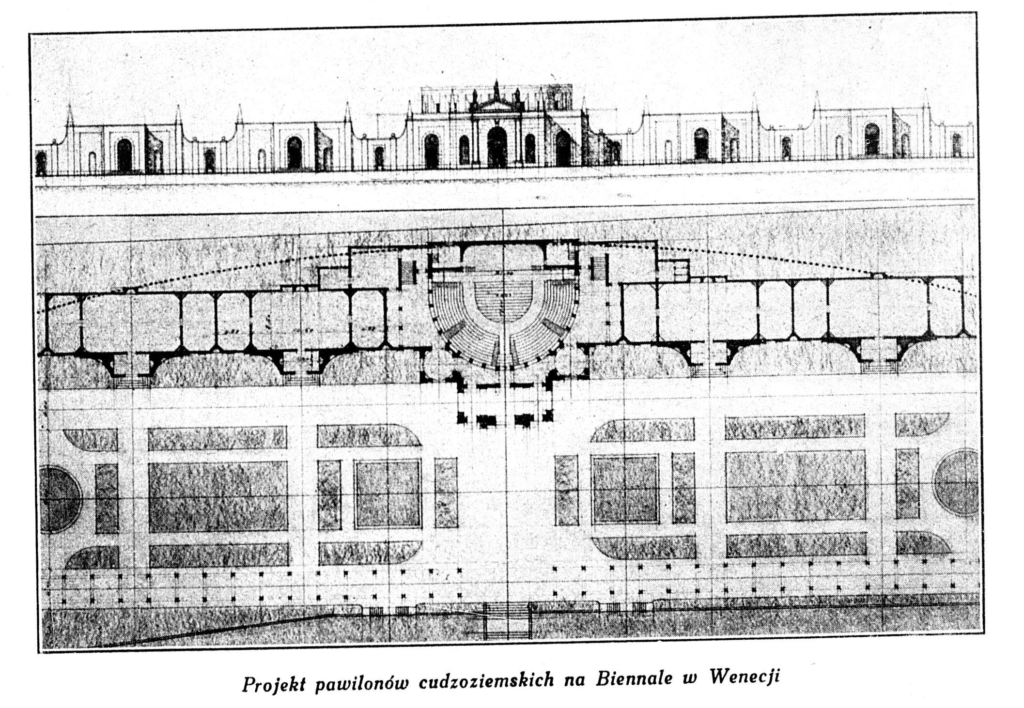

7. Brenno Del Giudice, design for the pavilions on Sant’Elena Island, façade and floor plan, 1930, from: ‘Polska na XVII-tej Biennale w Wenecji’ [interview with Wacław Husarski], Tygodnik Ilustrowany, no. 40, 1930, p. 842

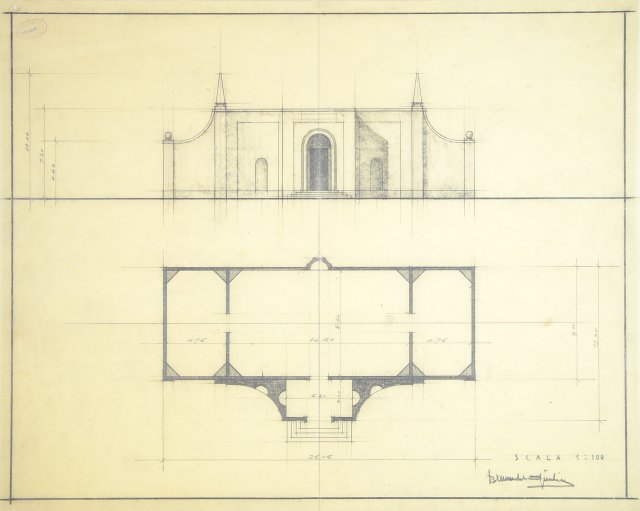

In 1930 the architect submitted a proposal for a long, narrow structure, conceived as a kind of screen to close off the perspective and mark the boundary between the exhibition and the city[32] (ill. 7). The scale of the building set it apart from the other Biennale buildings. Preceded by stairs, elevated a meter above its surroundings, it was composed of a central break flanked by four side breaks, arranged symmetrically on both sides. The central pavilion was particularly impressive, owing to its larger dimensions and more decorative elevation. In this version of the design three entrances were meant to lead to the central, bossaged part, and one to each of the side parts. The main entrance, situated between the facades, was meant to be embraced by semicolumns supporting jerkin heads decorated with three sculptures. As the floor plan of the complex shows, a theatre was initially planned to be located in the central part of the building. The architect planned to decorate the side elevations of the wings with decorative balls and pyramids (at the tops of the walls), pillars and niches (ill. 8). These decorations call to mind modern garden architecture. Del Giudice planned to break the monotony of the facade with high show entrances in the wings of the building, with a floor plan cut off straight from the front and joined to the side walls of the pavilion with an arched line. Behind the historical facades were to be modern exhibition venues – high, spacious, with no permanent divisions and with natural overhead lighting.

8. Brenno Del Giudice, design for the Polish Pavilion, façade and floor plan, 1931, ASAC

Each of the establishment’s five pavilions was built separately (ill. 9). The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs approved the architectural design in July 1931. Ambassador to Rome Stefan Przezdziecki stated that ‘the Ministry’s wishes have been satisfied in terms of … the choice of pavilion, found on the right-hand side, facing the central hall’. Consent was not granted, however, when it came to moving the building’s rear wall, which the department also tried to achieve.[33] The investment transpired in two phases. First, in 1931–1932, the central pavilion was built (originally for the decorative arts, presently Venetian) and the Polish and Swiss (presently Egyptian) pavilions on either side. The complex was completed in 1938, with the erection of two outlying pavilions for Romania and Yugoslavia (presently Serbia).

9. Building the Polish Pavilion, 1932, ASAC

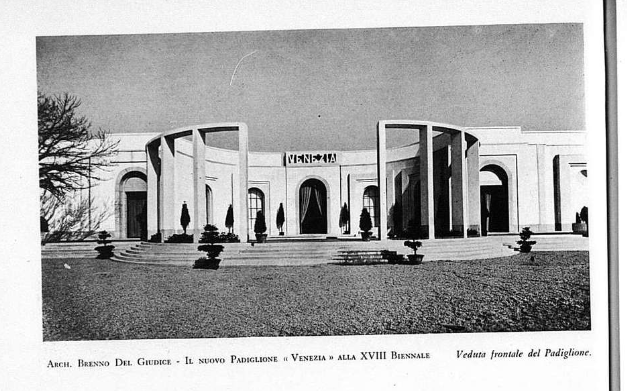

Working on the pavilion design, Del Giudice went the way of gradual stylistic reduction, as Marco Mulazzani has shown.[34] In the working design he simplified the elevation and forewent the historical decorative components, making the finished structure a far cry from the aesthetics of a palace of art (ill. 10). The most vital change with regard to the original concept was the modification to the central part of the building (ill. 11). It acquired an exhibition function, like the other pavilions in the establishment, yet it retained its dominant significance in the composition of the building as a whole. Its semicircular facade is pushed back, creating an exedra of sorts. There was originally an oval pond in front. The arc described by the line of the elevation was continued through the slender pillars joined by a cornice. The result was an elegant building with surprisingly slender proportions given the height and spread of the facade. Its restrained forms point to its basis in Italian rationalist architecture – especially in its Milanese geometrical rendition[35] – and yet its strong roots in tradition. The white surface of the elevation was enlivened with arches and rectangular frames. The gravity of the structure’s function is stressed by the block letters placed over each of the five main entrances. According to Chiara Di Stefano, in this design Del Giudice was seeking ‘a post-neoclassical symmetrical order’.[36] These aspirations corresponded with an architectural language used in the official investments of the fascist state.[37] Yet this remarkably long building has none of the weight of those designs. The distinction between the height of the facade, the partitioning of the structure, and the look of the elevation all work to bring a lightness to the building.

11. Brenno Del Giudice, Venice Pavilion, 1932, from: Ferdinando Reggiori, ‘L’architettura alla Biennale di Venezia’, Architettura, no. 7, 1932, p. 360

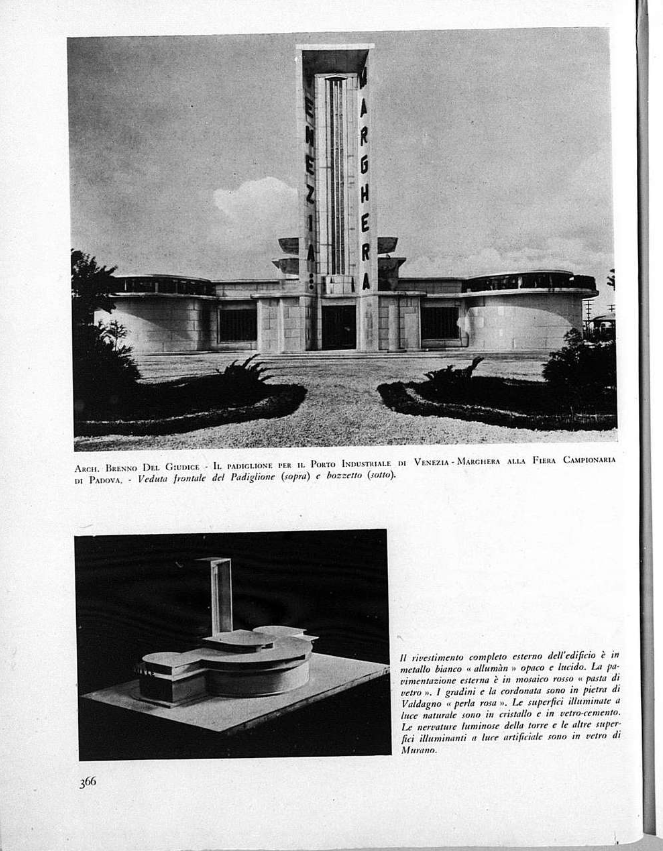

Subsequent designs show the architect skillfully adapter his proposals to his clients’ expectations. In 1932 he created the pavilion for Venice’s Marghera port at the fair in Padua (ill. 12, no longer surviving).[38] The forms he used here are decidedly more modern and expressive than the subdued language of these buildings on the Giardini grounds.

12. Brenno Del Giudice, pavilion for the Marghera port of Venice at the fair in Padua, 1932, from: P[linio] Ma[rconi], ‘Il Padiglione per il porto industriale di Venezia-Marghera alla Fiera Campionaria di Padova’, Architettura, no. 7, 1932, p. 366

The assumption of the pavilion and later changes

The architectural design of the Polish Pavilion received no commentaries in the domestic press, but in reports on the planned construction from the building’s opening, the very fact of holding a permanent exhibition space was perceived as a success. The Polish government was satisfied with the building, as shown by Secretary Maraini being honored with the order of Polonia Restituta ‘ex re the construction of the Polish Pavilion’.[39] The complex of five pavilions remains the major work by Brenno Del Giudice on the Biennale grounds. The design is an interesting (and to this day, the only) attempt, with aesthetics in the spirit of the epoch, to regulate the planning of the Venice exhibition through adding a new zone to the existing, picturesque, and somewhat haphazard layout of the pavilions – clearly on an axis and subordinate to a guiding compositional principle. This idea was carried out in full. The outer wings of the building were meant to be completed by the governments of Austria and Greece, who, in 1934, however, refused to accommodate themselves to the Biennale organisers’ suggestions, and gained permission to build free-standing structures on Sant’Elena Island (nos. 14 and 15 on the map). The Biennale Council decided that the presence of these countries at the exhibition was more valuable than the stylistic unity of the pavilions.[40]

The architectural idiom of the Polish Pavilion is undoubtedly more universal than the language of the creators’ initial concept, and it is probably for this reason that the building has remained mostly intact to this day. Although in 1957, the Biennale Council proposed the co-owners tear down the complex built by Del Giudice (the architect, incidentally, passed away that year) and erect in its place separate national pavilions, this plan fell through.[41] This idea was motivated by technical and exhibiting concerns, yet perhaps the scale and formal language of the building were too evident reminders of the fascist regime? Another solution was taken, which allowed the number of national representations at the Biennale to grow, and Del Giudice’s monumental concept to be subdued: In place of the pond and the extended open-work ‘arms’ of the Venice pavilion, the Brazilian pavilion was built in 1964 (designed by Enrique E. Mindlin, Giancarlo Palanti and Walmyr L. Amaral, no. 25 on the map).[42] IIn 1998, the Polish Pavilion was put under legal protection by the local conservation council, and thus cannot be torn down or rebuilt.[43]

Conclusion

The Polish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is a symbol of the ambitions of inter-war Poland in the arts. The decision for its construction, set in the realities of inter-war Europe, expressed a strategic attempt to strengthen the country’s position on the international arena by promoting domestic art. Poland remains one of twenty-eight foreign participants who have their own exhibition venues in Giardini. The pavilion’s construction guaranteed the country’s permanent presence in the prestigious company of the original national representations, while other countries that joined the exhibitors later on must try to find an exhibition space outside the main grounds of the Biennale.

Despite the passing of years and the changing socio-political contexts, the pavilion retains its significance as a testimony to the young nation’s strivings to build a modern image. Although the architectural form of the building is recognisably Italian and rationalist, it also corresponds to the identity and aspirations of Poland’s inter-war cultural policies.

[1] On Polish artists at the Biennale before the creation of the Polish pavilion, see Joanna Sosnowska, ‘Zanim powstał pawilon 1895–1930’, in Polacy na Biennale Sztuki w Wenecji 1895–1999, Warsaw: IS PAN, 1999. See also Mieczysław Treter, ‘Uwagi na temat XVII Biennale’, Sztuki Piękne, no. 9, 1930, pp. 306–310. The quote in the present article’s title comes from Treter: ‘Sztuka polska na międzynarodowej wystawie w Wenecji’, Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny, no. 88, 1932, p. 9.

[2] On the architecture of the Belgian and Hungarian pavilions, see Marco Mulazzani, Guide to the Pavilions of the Venice Biennale since 1887, trans. Richard Sadleir, Milan: Electa, 2022 (1st ed., 1988), pp. 38–47.

[3] Władysław Kozicki, ‘Sztuka współczesna w Wenecji’, in W gaju Akademosa. Poezje i szkice krytyczne, Lviv: Towarzystwo Wydawnicze, 1912, p. 144. See Sosnowska, p. 25. On the architecture and numerous reconstructions of the Italian pavilion, or the Palazzo Centrale, see Mulazzani, pp. 24–33.

[4] As Joanna Sosnowska points out, sympathy for the Czechs and Poles may have arisen from the Italians’ anti-Austrian bias; Sosnowska, p. 22

[5] See ibid., pp. 29–30

[6] See ibid., pp. 30–35. According to Mieczysław Treter, the Polish exhibition might have been shown in the German pavilion by the good graces of Giulio Baradela, financial inspector at the Biennale; see Archive of New Files (hereafter: AAN), Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Warsaw (hereafter: MSZ), no. 8717 – M. Treter’s note to the MSZ Press Department concerning badges for A. Maraini and G. Baradel of 23 August 1935, pp. 186–187.

[7] See Mulazzani, pp. 48–50.

[8] AAN, Ministry of Religious Confession and Public Education in Warsaw (hereafter: MWRiOP), no. 7059 – a transcript of W. Jarocki’s letter to the Ministry of Art and Culture of 7 June 1920, pp. 130–131.

[9] AAN, MWRiOP, no. 8/7059 – transcript of Jan Heurich’s letter to the Ministry of the Treasury of 15 December 1920, pp. 132–133

[10] Kurier Polski, no. 159, 1920, p. 4.

[11] Treter, p. 308.

[12] On disadvantageous changes in the ministerial structures to support Polish culture, see Sosnowska, pp. 37–38, and Konrad Winkler, ‘Bilans sezonu’, Polska Zbrojna, no. 203, 1932, p. 7..

[13] Zofia Norblin-Chrzanowska, ‘Polska na wystawie weneckiej’, Kurier Warszawski, no. 208, 1930, p. 18. On the Biennale’s rising significance, see, for instance, Zofia Norblin-Chrzanowska, ‘Przed “Biennale” wenecką’, Kurier Polski, no. 350, 1925, p. 8..

[14] This phrase comes from: AAN, MWRiOP, no. 7059 – certificate for Feliks Richling, delegate from the Ministry of Art and Culture for the picture collection, 22 January 1920, p. 116

[15] Sosnowska, pp. 41–44.

[16] Treter, p. 310. See AAN, MSZ, no. 8716 – Transcript of a note sent by the director of the MSZ Press Bureau to the Art Department of the Ministry of Religious Faith and Public Education, 20 May 1926, p. 78.

[17] Treter, p. 312.

[18] Mieczysław Treter made an acid remark on the show opened in the course of the exhibition in two rooms of the main pavilion: ‘Pawilon sztuki polskiej na XVIII Biennale w Wenecji’, Sztuki Piękne, no. 3, 1933, pp. 90–91..

[19] ‘Polska na XVII-tej Biennale w Wenecji’ [interview with Władysław Husarski], Tygodnik Ilustrowany, no. 40, 1930, p. 843.

[20] See Wystawa paryska 1925. Materiały z sesji naukowej Instytutu Sztuki PAN, Warszawa, 16–17 listopada 2005 roku, ed. Joanna Sosnowska, Warsaw: IS PAN, 2007.

[21] On the work of Brenno Del Giudice, see Giovanni Bianchi, ‘Brenno Del Giudice: una “moderna” tradizione’, in L’architettura dell’“altra” modernità. Atti del XXVI Congresso di Storia dell’Architettura (Roma, 11–13 aprile 2007), ed. Marina Docci, Maria Grazia Turco, Roma: Gangemi, 2010, pp. 268–279; Vittorio Pajusco, ‘Brenno Del Giudice e Duilio Torres architetti della Biennale’, in Lo Iuav e la Biennale di Venezia. Figure, scenari, strumenti, ed. Francesca Castellani, Martina Carraro, Eleonora Charans, Padova: Il Poligrafi, 2016, 29–48; Vittorio Pajusco, ‘Una segnalazione. Brenno del Giudice e Guido Cadorin il Gruppo per l’Architettura e Arredamenti di Venezia’, in Gli artisti di Ca’ Pesaro e le esposizioni del 1919 e del 1920, ed. Stefania Portinari, Storie dell’arte contemporanea 2, Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, 2018, pp. 479–486.

[22] Pajusco, pp. 479–483.

[23] Ibid., p. 483; Bianchi, p. 269.

[24] Bianchi, p. 269; Pajusco, Una segnalazione …, p. 484.

[25] Bianchi, pp. 270–271.

[26] Ibid., p. 270.

[27] Pajusco, pp. 29–30.

[28] Ibid, p. 31.

[29] Ibid., p. 33.

[30] An in-depth description of Maraini’s activities as secretary general of the Biennale is provided by Massimo De Sabbata: Tra diplomazia e arte: le Biennali di Antonio Maraini (1928–1942), Udine: Forum Edizioni, 2006.

[31] Pajusco, p. 35.

[32] The designs for Del Giudice’s complex of five pavilions are stored in the Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee della Biennale di Venezia (hereafter: ASAC), Padiglione Venezia, no. BIAP/1/28. See the pavilion designs reproduced in Mulazzani, p. 79; Bianchi, p. 272. See also Antonio Maraini, ‘La XVIII Biennale d’Arte a Venezia’, Il Tevere, no. 233, 1931, p. 3; Ferdinando Reggiori, ‘L’architettura alla Biennale di Venezia’, Architettura, no. 7, 1932, pp. 360–364; Pajusco, p. 38; Laura De Rossi, ‘Brenno Del Giudice ai Giardini della Biennale: 1932, il Padiglione Venezia – 2011, il suo recupero’, Arte Documento, no. 27, 2011, pp. 186–191; [s.a.], ‘Pawilon Polski w Wenecji’, Magazyn Zachęta Online, no. 38, 2022, https://zacheta.art.pl/magazyn/pawilon-polski-w-wenecji-2/ (accessed 30 November 2024]; [s.a.], Historia Pawilonu, https://labiennale.art.pl/historia-pawilonu/ (accessed 30 November 2024).

[33] AAN, MSZ, no. 4342 – a letter from ambassador S. Przezdziecki to the Press Dept. of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concerning the Polish Pavilion at the Biennale of 11 August 1931, pp. 7–8.

[34] Mulazzani, p. 78.

[35] See Richard A. Etlin, Modernism in Italian Architecture, 1890–1940, Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1991, the ‘Geometric Novecento Architecture’ chapter.

[36] Chiara Di Stefano, Il fascismo e le arti. Analisi del caso Biennale di Venezia 1928–1942, an MA project written under the guidance of Angela Vettese, 2009, Ca’ Foscari, Venice, p. 82. https://www.academia.edu/7438955/Il_Fascismo_e_le_Arti_Analisi_del_caso_Biennale_di_Venezia_1928_1942 (accessed 2 December 2024).

[37] For more on Italy’s fascist architecture, see Il razionalismo e l’architettura in italia durante il Fascismo, a cura di Silvia Danesi, Luciano Patetta, Venice: Edizioni La Biennale di Venezia, 1976; Etlin, the ‘Modernism and Fascism’ chapter and Diane Ghirardo, Italy. Modern Architectures in History, London 2013, the ‘Architecture and the Fascist State, 1922–1943’ chapter

[38] P[linio] Ma[rconi], ‘Il Padiglione per il porto industriale di Venezia-Marghera alla Fiera Campionaria di Padova’, Architettura 1932, no. 7, 365–68.

[39] AAN, MSZ, no. 8717 – a note from M. Treter to the Press Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concerning an order for A. Maraini and G. Baradelo, 23 August 1935, pp. 186–187.

[40] De Sabbata, pp. 97–98; Pajusco, pp. 39–40.

[41] See ASAC, Lavori e gestione delle sedi. Padiglioni 2 – transcript of a letter from Biennale head Alesi Massimo to Polish ambasador in Italy Jan Druto of 30 January 1957. I thank Anna Kowalska from the Biennale Bureau in Zachęta – National Gallery of Art for providing the materials for the investigations I made in this archive.

[42] Mulazzani, pp. 127–129.

[43] Sixteen national pavilions were placed under protection at this time: Vittoria Martini, ‘A Brief History of How an Exhibition Took Shape’, in Starting from Venice. Studies on the Biennale, ed. Clarissa Ricci, Milan: Et al., 2010, p. 73, note 38.

Financed by European Union NextGenerationEU