37,1 (cont.)

Mirosław Bałka

Galleries are intended for art as hospitals are intended for disease. Approaching them, we are aware of their distinct and special status. Simultaneously, we are accompanied by vague expectations, most often linked to our expectation of discovering some truth, or meeting a significant fact face to face. But art, just like disease, breeds almost unnoticed. Sometimes a tiny detail is decisive, some small disturbance — a single line on the thermometer scale, an impractically placed object, a slight alteration of proportions. Those objects which in the process of their creation assimilate reality outside art are the hardest to qualify. They cease to adhere to closed definitions and to the works which they represent. Their description can be completed by the way they coexist with other objects, substances and notions. Thus we discover them in different circumstances, in which they undergo a process of defunctionalization almost before our very eyes. Sometimes it is precisely this loss of function which gives a particular work its significant persuasive power, bringing back the importance and relativity of related notion and exposing the essence hidden by the habit of function.

“Pavilion (from the French pavilion – tent) – 1. A small, free-standing building of light construction. Scattered among greenery in baroque gardens, they served for relaxation, meetings and social entertainment; 2. A separated part of a building (especially a palace) having a complex shape and a separate roof.” (Mały Słownik Terminów Plastycznych, WP Warszawa, 1974, page 266)

The tent, the prototype of a pavilion, is the simplest of all constructions meant to provide human shelter. It ensures neither actual nor imaginary protection as do fortresses (since they are the result of the growing complexity of human relations). It is not abiding place, like the caves of Altamira, which were inhabited by man out of the primitive animal instinct of fear and which became the archetypic gallery, a place mark-d for art. Thus, is it the sense of safety or is it fear which breeds art?

The tent, in its original function of providing immediate, makeshift shelter, once became an object of interest for the artist. He joined two steel plates together so that they formed an equilateral triangle together with the floor. Steel tents are not used for camping, nor do they feature in the history of mankind. Steel has its own mythology, dominated by such notions as hardness, stiffness and impenetrability, filled by the clangor of arms and the roar of war machinery. The outcry “Beat thy swords into plowshare?” reveals an ambivalence of intentions. “He who fights with the sword shall die by the sword” — that which protects also destroys. The spiral of invention based on this conviction has so exceeded human dimensions that sometimes it seems unbelievable that man originally created it for his own safety.

The Polish Pavilion in the Giardini di Castello in Venice stands sandwiched between the Italian and Romanian properties. It is a typical example of European architecture from the mid-thirties — a phase when Art Deco, having recoiled from austere functionalism muffled its anthropometrism, grew gigantic in size and petrified, as if in an effort to harmonize with the size of the uniformed columns stalking the streets of Rome and Berlin. It was a reaction to the breathtaking concept of the übermensch, who reaches above the glitter and chaos of the crowd, just as the walls of the pavilion loom over the fragrant tiny-leafed acacia trees and the mindless humming of cicadas.

The interior is narrow and high, as if attached to the facade by accident, then cut off along its parallel axis before expanding the possibilities foreshadowed from the outside. These are emphasized by the existence of an entryway sliced symmetrically into two semi-circular niches. The design of the structure, with its categorical linearity, accentuates the disproportion between the open space of the room and the shape of the entryway, which is too organic, provoking intervention and full expression. The two parallel lines extending from the entryway to the interior of the pavilion unexpectedly introduce relativism into our perception of the whole. The entryway acquires genital features and organic prolongation into alien territory; a common yet separated area for both parts, the outer and the inner, is thus formed: an open and passable vessel, an epistemological tunnel, a way of diffusing inside, the foreshadowing of knowledge.

When the two parallel lines leading from the entryway inside the pavilion are translated from drawing to reality, they form a corridor 8 m long. Its walls are covered with a layer of soap to the height of 190 cm.

“Soap, salts, most frequently derived from sodium (less often from other alkaline metals) from saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, obtained by washing off animal fats (mainly tallow) or solidified plant oils, often enriched with coconut oil and resin. Soap is the first known surface active substance; commonly used for washing and in technology.” (Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN, Warszawa 1974, p. 207)

“Surface-active substances, a group of chemical compounds, whose molecules consist of two elements with reverse affinity to water, the hydrophobic element and the hydrophilic element. In practice, the greatest significance is given to anionic active and non-ionic compounds; their share in the general production of surface active substances exceeds 90% … Cationic active and a few amphoteric compounds have powerful bactericidal properties and are used, for example, in disinfection.” (ibid. p. 664-665)

“Lysol, a pharmaceutical cresolic liquid soap, reddish-brown; a transparent cresol-scented liquid containing about 50% cresol; a powerful disinfectant and antiseptic used for disinfecting hands (a 1-2- solution) and medical tools (a 5- solution); today used mainly in veterinary medicine due to its irritative properties and strong smell.” (Encyklopedia Powszechna vol. III, p. 743)

In everyday life, in an area remote from epic battlefields and eschatological disputes, a growing demand exists for certain articles on the market. This demand particularly concerns food and cleansing products, especially soap. Long – lasting, unsatisfied needs create a habit of industriousness, which sometimes stays forever. That is why one often accidentally finds odd pieces of dry soap ends in the homes of elderly people. Apparently it’s easy to use them by the simplest home methods.

The process of presenting reality through art is a euphemistic procedure often consisting of metaphysical diversions somewhat like magic. Actions sublimate into signs of actions, and the objects of art receive the stigma of resembling objects outside art. The process is similar to photographing reality: first we obtain a negative, i.e. a picture twice reversed — a mirror reflection (right is left) and a light opposite (black is white and white is black). The negative, a transitory form, thus carries a reverse picture. From it we obtain a print which is a remote memory of reality. Faithful reconstruction of reality is not possible even if we retain real – world scale and dimensions. For this reason, type use of quotation marks becomes necessary. The gallery walls play that role for art.

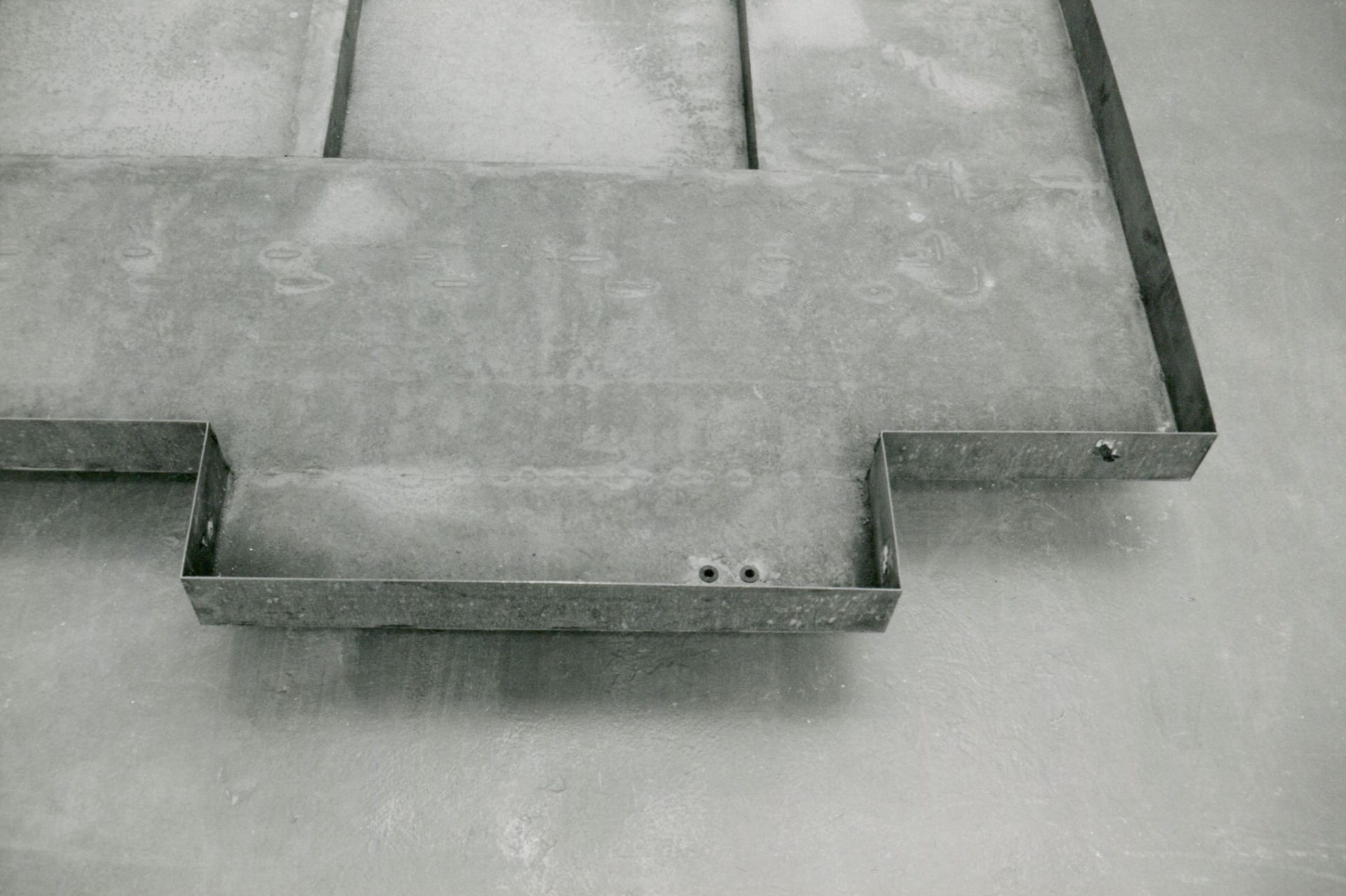

Terrazzo — artificial stone derived from cement, containing pebbles (most often marble)- In Poland it is most often used as a building material (for example, for window sills and kitchen and bathroom floors), as well as in the production of tombstones. Mirosław Bałka uses it as a medium for sculpture.

Canon. God created man in his own image. But the God who lives in each one of us does not have a single face and concrete dimensions. God is ideal. Man is a model for himself- He creates aesthetic and ethical canons in which his human disability may reflect divine perfection. The ideal man in the interpretation of Polyklete of Argos (450 -415 B.C.) was bulky. Measuring 156 cm, his Doryforos would have a child’s hand, a huge head and shoe size 41. When Lizyp accepted more slender proportions, resembling perhaps the shape of an Ionic column, he could have been trying to approach the ideal of “homo quadratus”, which Vitruvius inscribed in a circle and to which Leonardo gave his blessing several centuries later. Le Corbusier’s model crammed us into a great slab of “machines for living”, lowering the ceilings to such an extent that Bałka instinctively bows his head when entering a “conveyor – belt” apartment. The canon, like dogma, does not bring us closer to God. However, it can function as a point of reference in getting to know ourselves. Bałka is 190 cm tall.

The Grandparents’ home does not comply with Le Corbusier’s model. It has its own scale, optimal for those engaged in its construction, minimal for its heirs. The arrangement of rooms complies with the building customs of provincial Poland, in which the kitchen is the hub, the heart and soul of the house. It is the First Room, the room just beyond the threshold, the purgatory, in which a number of transformations take place: processing food, cooking meals, eating, washing, scrubbing, changing clothes and shoes. It is the command and selection center, which permits passage to other rooms of the house. The doors to the right and left open to safe, peaceful and intimate spaces, to well arranged customs and hierarchies of holy pictures and wedding portraits. There is furniture, the most important of which are the beds: warm and soft tuck-away places for the body. A third way out leads through a square opening in the floor. A heavy trapdoor seals the entrance to the cellar where food and preserves are stored. In extreme or dangerous circumstances the cellar could even serve as shelter or hiding place. But then the trapdoor would have to be better concealed. The floor covering, for instance, could be loosely spread over it instead of being laid according to its shape. The wardrobe could stand on top. Or a table. The warm area wouldn’t be cut off at the surface, but could reach beneath.

“Constant body temperature, homoiothermy, the ability to maintain a constant body temperature, independent of the temperature in the environment one of the adaptation mechanisms of an organism to its environment facilitates the intensification of metabolic and many other processes, independent of the time of day or year, and facilitates the control of various environments.” (Encyklopedia Powszechna, vol. IV, p. 261)

The optimal temperature of the human body in Europe is 37 degrees Centigrade. Fever is indicated when the temperature rises one degree. In Poland, fever begins at 36.7 degrees. Poland’s norm is lower.

The holy pictures, wedding portraits and beds are all gone from the Grandparents’ house in Otwock. Only absence has stayed behind as the piercing reality of this place. Absence, as a real condition, cannot be transferred to some other place.

“Critical temperature the temperature of a one – component physiological system in a critical state, i.e. in the state of balance between the steam and liquid phases when their properties become identical. A substance can exist only in the form of gas in a temperature exceeding the critical one.” (Encyklopedia Powszechna, vol. IV, p. 464)

A grass covered yard stretches between the Grandparents House and the shed which houses the artist’s studio. Until recently, the space was dissected by a steel rope hanging between the trees. When walking beneath it, the artist had to bend a bit.

“The fate of the children who realized they had to die was horrible. Because only the smallest were selected, the children, when approaching the pole hung at the height of one meter twenty centimeters, straightened up, walked on their toes to touch the pole and save their lives.” (Zofia Nałkowska, “Medaliony”. Children and Adults in Auschwitz)

Zofia Nalkowska’s “Medaliony” is required reading in Polish secondary schools.

Some people are convinced that a description of the world deprived of the artist’s commentary is incomplete and strangely inadequate. Let us therefore think about the difference between a statement (which by definition is objective and as close to facts as possible, i.e. rational, easily judged and proved) and performance, or the recreation of an insignificant fragment of a larger whole. Let us imagine that a friend rings at our door and recounts how a downpour caught him on the way home and soaked him so much that water still flowed from his clothes. We know from the radio as well that it was raining. But another friend enters the house marking his steps with puddles of water. He wrings his shirt, pours water out of his shoes. Does he need to say that he was stuck in the rain? Does the power of art necessarily consist in the directness of a message told by someone in first person, or in a subjective message of visual presentation of facts and rendering them through their physical actuality. In reality, the information we receive in this case does not pertain to the world so much as it does to the artist himself. He is the object of creative work, just like the work itself is the object of art. Associations to the world outside the work and the artist boil down to gaining knowledge from other sources (we know it was raining from the radio). If we ignore our knowledge, facts lose their logic. We stand before a situation extracted from life, created for its own sake in an appropriate place also separated from everyday existence, in which objects relate to one another in an ambiance of subtly balanced lengths and proportions, in a dialogue of materials and an insignificant evolution of form. The only intrusion into this world of aesthetics is the smell of soap, with the slight addition of nauseating lysol, perhaps. But even if we stay in the world of aesthetic relations we might want to find the answers to some questions. Why do some objects lie, for instance, while others stand? Why are some hung, instead of just existing? Why is one form a negative matrix of another? Why are some of them made of steel and some of terrazzo? Why are some of them “naked” and some “clothed”, some cold, others warm?

“Allegory (Greek “alios agoreio” — to say differently) a figurative depiction of certain notions and ideas in a work of art. Thus fame or the vanity of human existence can be depicted conventionally through a symbol, personification and accompanying attributes and signs, etc., sometimes forming a complicated whole. An allegory may also be created through arrangements of objects and persons lacking conventional meaning, but encouraging the search for hidden meanings on the basis of revealed relations between the parts of the composition and the ideas to which the composition alludes. A characteristic feature of allegory is its lack of fixed meaning, thus requiring interpretation. …”(Mały Słownik Terminów Plastycznych, W.P., p. 20-21)

Anda Rottenberg

List of the works at the exhibition:

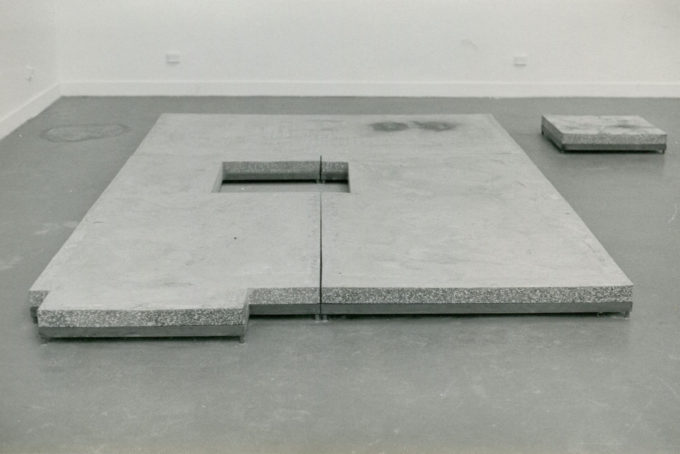

- “367x241x25” steel, carpet, soap, 1993

- “100x50x52, 100x50x52, 350x230x23, 0 0,4×810” steel, carpet, soap, sediment, ash, felt, 1993

- “190x60x10,190x60x10,380x230x13,69x67x13” steel, terrazzo, carpet, heating cables, wood, ash, felt, 1992/93

- YEAR1993

- CATEGORY Biennale Arte

- EDITION45

- DATES14.06 – 10.10

- COMMISSIONERAnda Rottenberg

- CURATORAnda Rottenberg