Symbolic Weapon IV

Zofia Kulik

The decision to show Zofia Kulik’s work in the Polish Pavilion at the 47 International Biennale of the Visual Arts in Venice is a function of more general considerations.

The question which comes to mind can, in short, be formulated thus: is it possible today to restore in art a more universal axiology which is not reduced to formal tautologies, historical quotes or the individual, frequently anarchic choice of a single artist? (A choice predetermined by a private “history”, the “personality” or private interest of an artist entangled in the strategies of the art market.) We are therefore trying to envision the possibility of existence of a world of standards and values which are not merely reduced to practical and technical actions, such as using a VCR, or even the rules of marketing, but which embrace something which once upon a time was unabashedly called personal values or, even more quaintly “transcendental values”.

Many people today are asking themselves this question – many critics and artists searching for a way out of the post-modernist trap. I shall focus on quests inspired by the ideas which, at the beginning of the 20th century, instilled a new cultural and social vitality into art, and which can generally be termed ideas of the Grand Avantgarde. It is now accepted that they, by deepening the erosion of religious attitudes, have in the second half of the 20th century succumbed to a characteristic and inevitable atrophy culminating in today’s post-modernist torpidity in art. But the problem, I think, is more complex than that, as the case of Zofia Kulik will demonstrate.

Let us start by stating that the art world has been witnessing radical criticism of post-modernism from a modernist viewpoint for a long time now (not that modernist positions were ever completely abandoned). Today, though it may sound paradoxical, one could even speak of a conservative backlash on the part of the avant-garde, trying to regain its former, prominent positions at least since the end of the eighties. These returns take on many varied guises, just as art-moderne was varied and diverse.

Seen against this background the work of Zofia Kulik seems a complex case indeed. Elements of avantgarde philosophy, acquired during her studies under Oskar Hansen and reinforced by certain axiologic and artistic decisions made in the nineties interlace with a post-modernist experience evidently at odds with the avantgarde.

Oskar Hansen is one of the key figures in Poland’s post-war art culture. The mentor of several generations of artists, guardian of the ethos of the Grand Avantgarde, especially of the values on which its “bright side” hinged a belief in the intelligibility of the world and in its susceptibility to positive reconstruction without the necessity of limiting the freedom of the individual.

Conspicuous among the ideas Kulik took away from her studies with Hansen is certainly the conviction that the work of art is a way of solving a complex problem, rather than a means to express one’s moods, states of mind and fascinations, and that art is always secondary to some outside world, some reality, some environment which should be perceived, described, or even laid out as a plan, model or sketch. To be an artist one must study one’s surroundings using all available means such as sketching, modelling, photography. This approach also favours modern techniques of registering reality; allowing for new forms, new tools of discovery. (The camera is one such tool and in the work of Zofia Kulik it has played a key role).

Among other notions passed on during studies with Hansen and easily relatable to the main notions of the avantgarde, we must definitely place social sensitivity, a polemic and rational attitude; seeing the world as inherently structured, capable of being defined in its internal relations and associations; with a respect for time and temporality being one of the key categories and one of the most important factors shaping reality and our perception of it. At the source of Hansen’s conception of open form was a vision of man as the autonomous subject of all worldly processes, impossible to con-fine in any ideology or religion. It relies on a belief in humanity’s fundamental freedom of choice in the process of creative interaction with its surroundings. The artist may not create, symbolize nor promise any truths or ultimate conditions. He or she may only create “screens”, supply a backdrop for the free decisions of the autonomous human being.

In her student days, and for some time afterward, Zofia Kulik produced hundreds of slides. In terms of both content and technique they represent a distinctive, individual transformation of the above-named ideas. The subject of her analysis are the surroundings, objects, situations and matter, with the camera being the tool of a observation and documentation. It is, however, neither the only nor a neutral participant in these operations. During each stage of this purposely drawn out process, the presence of the artist is as relevant as her permanent activity in relation to the “investigated” surroundings and to the photographic medium registering them. Thus, there is always a characteristic coupling of the subject, the object and the photographic registration. The photograph is a document of the registered surroundings, but also an active intermediary in the feedback between man and the world.

A clear expression of this artistic philosophy, and one important for the history of artistic ideas in Poland, came in the early stages of her work with a group film project entitled Open Form. (The fact that this was a group creation was in this case additionally justified.) The title relates to Professor Hansen’s concepts, while the film’s content was a permutations made independently by Zofia Kulik and the artists who worked with her.

The full extent of those ideas found an outlet in Zofia Kulik’s work in the seventies, especially during her collaboration with Przemysław Kwiek when, as KwieKulik, they formed the PDDiU (The Action, Documentation and Diffusion Workshop). During their work together the artistic transformation of reality via its visual document ceased to be a clinical idea tested only in the lab. The activities of Kwiek and Kulik ventured out into social space. The subject of the artists’ manipulations, for which they used ready-made objects taken from their surroundings, physical matter and the symbols of communist iconography was life under the ‘real socialism’ of Poland in the seventies. The idea of art as “backdrop” gained significance, subversively exposing the authoritarian reality without formal-ly engaging in an open, ideological disagreement with it. By accepting this reality and its propaganda slogans as genuine and to be taken seriously the artists made reality ‘creak’ in the cogs of the creative process and thus expose itself. Such an artistic orientation incurred consequences reaching beyond art, such as bans on exhibiting and travel abroad.

It is worth mentioning here that the actionistic activity of KwieKulik was substantially motivated by conceptualism which had a very strong impact on the attitudes of many Polish artists in the six-ties. The work of the PDDiU was analytical at heart. It ‘drained’ the work of its visual aspect, even though it was clearly present, maybe even more so than in the work of other Polish artists at the time.

And than in the eighties there came a fairly radical turn in the artistic forms and philosophy behind Kulik’s activity. In a discourse she obviously found difficult, she took a stand against her initial artistic and philosophical experiences. Among the justifications of such a move was her conviction that art had to become sterilized by conceptualism which rather one-sidedly engaged the mind’s analytical faculties while neglecting those areas which feed on the creative and inquisitive force of sensual representation. The reversion was also probably caused by a weariness of the artistic operations undertaken with Kwiek in the PDDiU which were albeit based on her own theory inspired by praxeology. Impatience with work in a very small domain, without the chance to create on a grand social scale, so desired by the avantgarde artist. Another cause according to Zofia Kulik was her objection to participating in process-based and ephemeral artistic rituals: actions, activities, performances and her growing need for a stable, “classic” objet d’art. A non-artistic cause would also have been the prostration of Poland’s state-run economy and centralized political system. During martial law “scientific socialism”, that peculiar outcrop of modernist philosophy, seemed repulsive, even to declared leftist artists and intellectuals. In 1987 Zofia Kulik again commenced to work on her own.

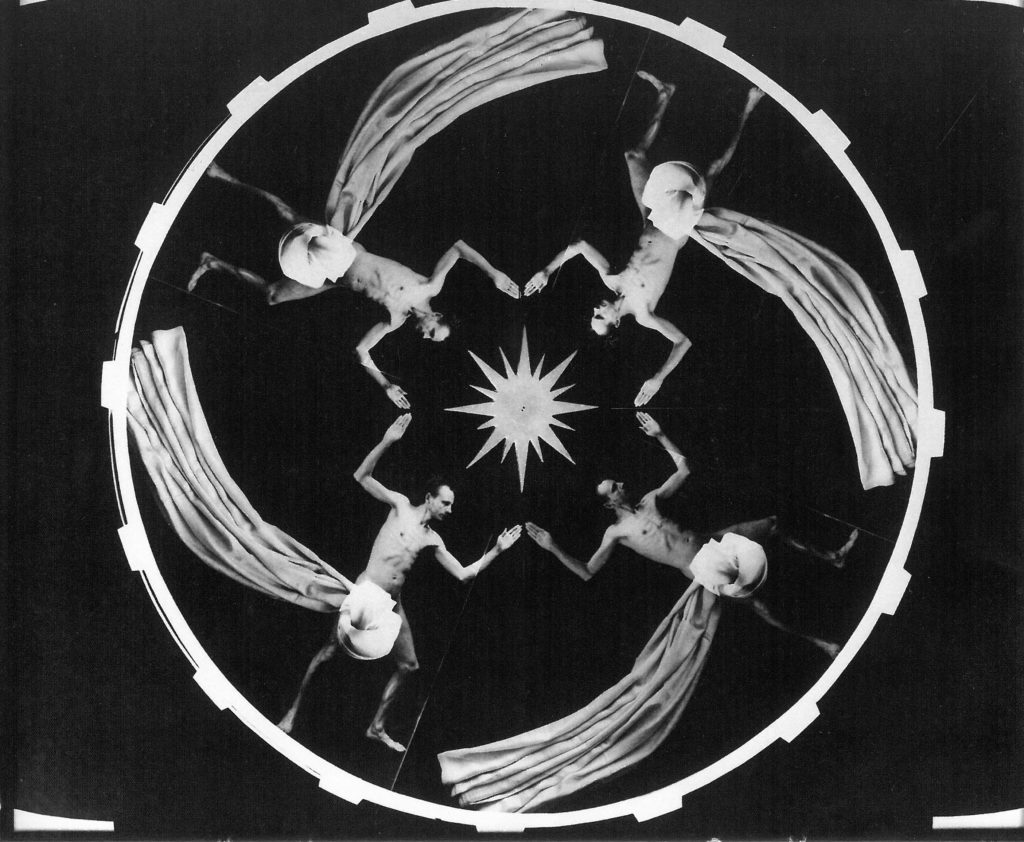

From that moment on her works were born of conflict, in conscious contradiction to earlier pieces. The objects then made were purposely “closed”. They broke off to some extent from the world of events and the reality around us, searching with their singular symbolic narration for a different, “eternal” existence. They were also radically different in their internal construction, generating hieratic, symmetric “designs” rather than structures. There emerged in them a kind of internal, symbolic interconnection in place of the former visual equivalent to the material world. It was as if the artist had ostentatiously abandoned everything that determined the form and the philosophy of her earlier activities. Her works took on the form of display cases: “closed” literally and metaphorically, recalling archaeological collections of objects from different cultures. Another strand were the shining objects -miniaturized burial mounds, obelisks, pyramids, monuments, mausoleums and above all – the monumental photo-carpets. Her former aptitude as a documentary photographer, refined the experience of having taken hundreds of thousands of pictures changed its utility and sense. No longer a means of maintaining the artist visual interaction with the world, it became the substance of artistic craft, which, above all, meant deliberately succumbing to the photographic process itself. In transforming the image of reality into a photographic one, she let herself be guided by the technique imposed by the light-sensitive material, the existence of the negative with its reversibility, and by the uncontrolled effects, enigmas and accidents that happen during the photochemical process. Chance had played an important role in open form, but for reasons entirely different than were the case in Kulik’s apocalyptically reversed new practices. Centrism, symmetry multiplication, order, figural ornament, forcing certain existing patterns and structures upon oneself – became the new principle of composition. What mattered now was not so much to reveal the mysteries of the real world, but simply the magic of the picture. The operations of exposure, masking, and uncovering subsequent fragments of photographic paper were meant to disclose not reality, but a mysterious meta-picture. Thus understood techné was the basis for constructing of grand photo-paintings which bring to mind a carpet because of their symmetry, ornamentation and the arrangement of motifs among which an important role the posed male figure plays. This almost classical model appears in the company of draperies, flowers and plants, like in a still life. Instead of the free man we have a man with a noose around his neck and a collection of the timeless motifs of power, violence, domination and war.

The artistic practice of Zofia Kulik in certain aspects mirrors the argument of the post-modernists with the modernists. In a cultural dimension, however, the altercation had a much broader character, and though it also took on neo-conservative forms which aimed to reconstruct certain elements of the artistic tradition, the end result surprised the conservatives and the leftist radicals both. What was undermined here, was the sum of European spiritual tradition in its modernizing version, which in the 20th century took on the guise of avantgarde art, as well as in all its other traditional costumes. The result was a dissipation of all shared narratives, and the ultimate supremacy of mass culture and market forces. (This uncertain ground is tentatively treaded by the third generation of artists, among them a kind of anti-Hansen in the person of Zbigniew Libera, Kulik’s pupil, model and inspiring force, who in his own work examines the ‘idiom’ of today’s commercialized pop culture. His position in this game is not clear, though, given his seeming vacillation between critical detachment and the lure of a world governed by the rules of marketing.)

The situation of many Polish avantgarde artists of the middle generation, including Zofia Kulik, became rather specific as the post-modernist condition of culture developed. Another contributing factor were the phenomena taking place in Polish social life after 1989 when, after the fall of the Iron Curtain Poland joined other market economy countries. In Poland, too, artists and society were faced with events brought about by post-modernism understood as a condition of culture. It ultimately stripped art of the power to convey humanist narratives out of which one could construct any collective meanings, and which provided some “metaphysical” justification after the “second disenchantment of the world”. Therefore, a return to neo-avantgarde positions becomes a return to values which, one way or another, provided a common, unfragmented perspective offering more than the possibility of playing with language in the free markets of culture.

Reality has faced artists with the question posed at the very beginning of this text. The answer which Kulik gives us is: it is possible to make art which relates to the universal, though already historic higher values which have upheld the concepts of the avantgarde. However} it is possible only in an individual fashion, empowered y one’s own decision and with the assumption that there is no one universal pool of values which might satisfy a common axiologic hunger, because the tension between common interest and variety of individual choice is irremovable.

Returns to modernist axiology therefore take on the character of individual “enchantments”; they are something of a spiritualist seance at which those values are evoked for the benefit of the few remaining spectators craving humanist thrills. They are a rather solitary effort to liven up remnants of an axiology different from the one overcome and trivialized by pop culture. Than again, the motivation need not be so pessimistic: one can hope that moral effort on the part of an individual may also bring about universal effects.

Today, Zofia Kulik once more sets her work in a modernist perspective, purposely alluding to earlier experiences from the seventies, negating, however, the fact that post-modernism had brought about some very significant and valuable changes took place, brought about by post-modernism. This means, among other things, that she objects to the now-current notion of art as egoistic self-expression, and refuses to accept the academic art of today, which fulfils itself in its aesthetic immanence. She treats art as the result of work in the face of present-day cultural codes. She links art to the necessity of investigating and documenting of the reality around us, its rationalization, as well as its transgression. What matters here, though, are specific options of behaviour, views on the artist’s role and place, denying to situate him or her in the framework of religious metaphysics or humanist myth, but also rejecting deconstructionist practices or the return to an avantgarde, anarchist mutiny which changes nothing but its context (e.g. class struggle supplanted by the battle of the sexes). This suspension between necessity and freedom is one of the most characteristic features of the current situation of artists in general and of Zofia Kulik in particular.

What has really remained of post-modernism in Zofia Kulik’s objects? Does not the merging of an avantgarde past with today’s striving to reconstruct certain elements of that past from the rubble of post-modernist experience of the eighties result in the emergence of some sort of “good old moderne”? My personal view is that the result of this many-stranded discourse which the artist carried on with the contemporary art world is an especially mature and complex set of artistic and aesthetic standards.

Above all, Kulik has not renounced the power and qualities of the image. Her monumental photographic carpets required of a traditional work of fine art. They fulfil criteria of the form in which they perform their symbolic functions; they are well-made, demonstrating a concern for permanence and compliance with the standards expected of museum-pieces. Actionism and ephemerality are absorbed by the image. This does not deprive the image of its ability to allude to the present. It does not deprive it of topicality and realism. The composition AU the Missiles Are One Missile, which is at the centre of the exposition at the XLVII Biennale in Venice does not refer us to some histories universalities but very clearly invokes dramatic events emanating from the pages of newspapers and television screens. Although Zofia Kulik treats concepts such as inspiration with detachment and even irony, and her photo-images are staunchly rational, leading critics to speculate about “conceptual carpets”, that rationalism, central to conceptualism, is mocked in those pictures, placed in brackets, called into doubt. The analytical rationalism of a theoretical mind is in a way censured. Rationalism is not the source, the driving force of this art. It is not its ideological alibi, but on the contrary becomes bloated, monumentalized by its symmetry, repetition, duplication, its emphasis of number series and geometric divisions. As such it has been incriminated, and the verdict is: totalitarianism.

The true hero in Kulik’s works is the differentiated mind. It is the craftsman’s techné, supported by intuition and the requirements forced upon us by the sensual form of the photographic image that come first. Theoria comes later. A praxis entangled in existence enables compassion and sensitivity to the position of others uncompromised by abstract, ideological models.

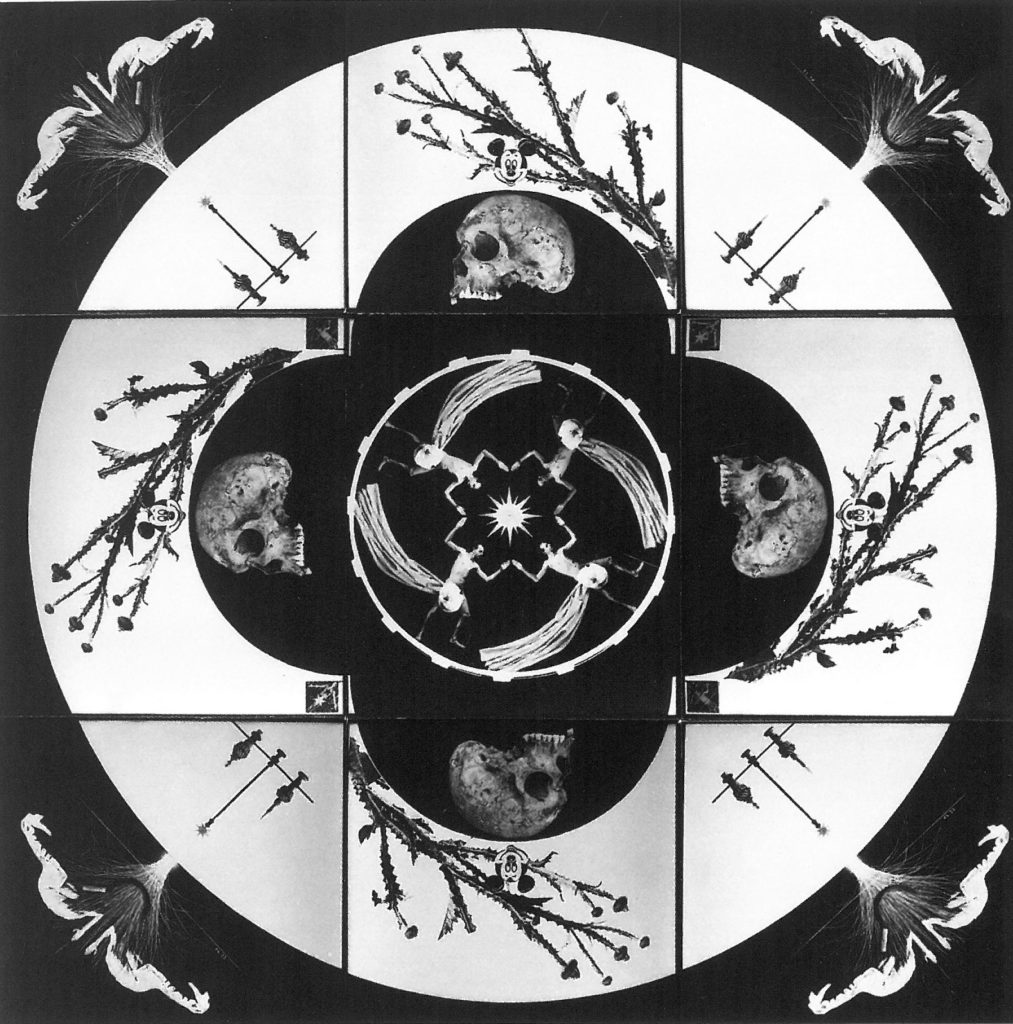

An important aspect in Kulik’s work, one which cannot be reduced to the ideological principles of modernization and which remains a legacy of the neo-conservative experience of post-modernism is “metaphysical sensitivity”. It is not a sensitivity taking on any religious form, some specific liturgy. It is rather something which accompanies every being placed before the inevitability of its own death and the painful transience of the world. Zofia Kulik combines this sensitivity with the praxis awakened within her, with the realm of the mind which is not responsible for mathematical and analytical operations, which facilitates contact with the poverty, humiliation and misery of this world. It is the mind: entangled in existence, close to the body, where her femininity feels best. A good example through which to analyse this sensitivity is the monumental composition on which Kulik is currently working, entitled Ethnic Wars. These are skulls laid out on dozens of brightly patterned kerchiefs owned by women from Bosnia or Chechnya.

In the end, the idea is to work out a role and place for the artist that would restore a humanist perspective: a faith in human freedom and in the potential of the human mind and in the possibility of transforming reality political reality included. It is also important that the acceptance of such a perspective does not lead to extremes: neither to avantgarde, anarchist mutiny nor to post-modernist nihilism.

Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski

- YEAR1997

- CATEGORY Biennale Arte

- EDITION47

- DATES15.06 – 09.11

- COMMISSIONERAnda Rottenberg

- CURATORJan St. Wojciechowski

Work on disply

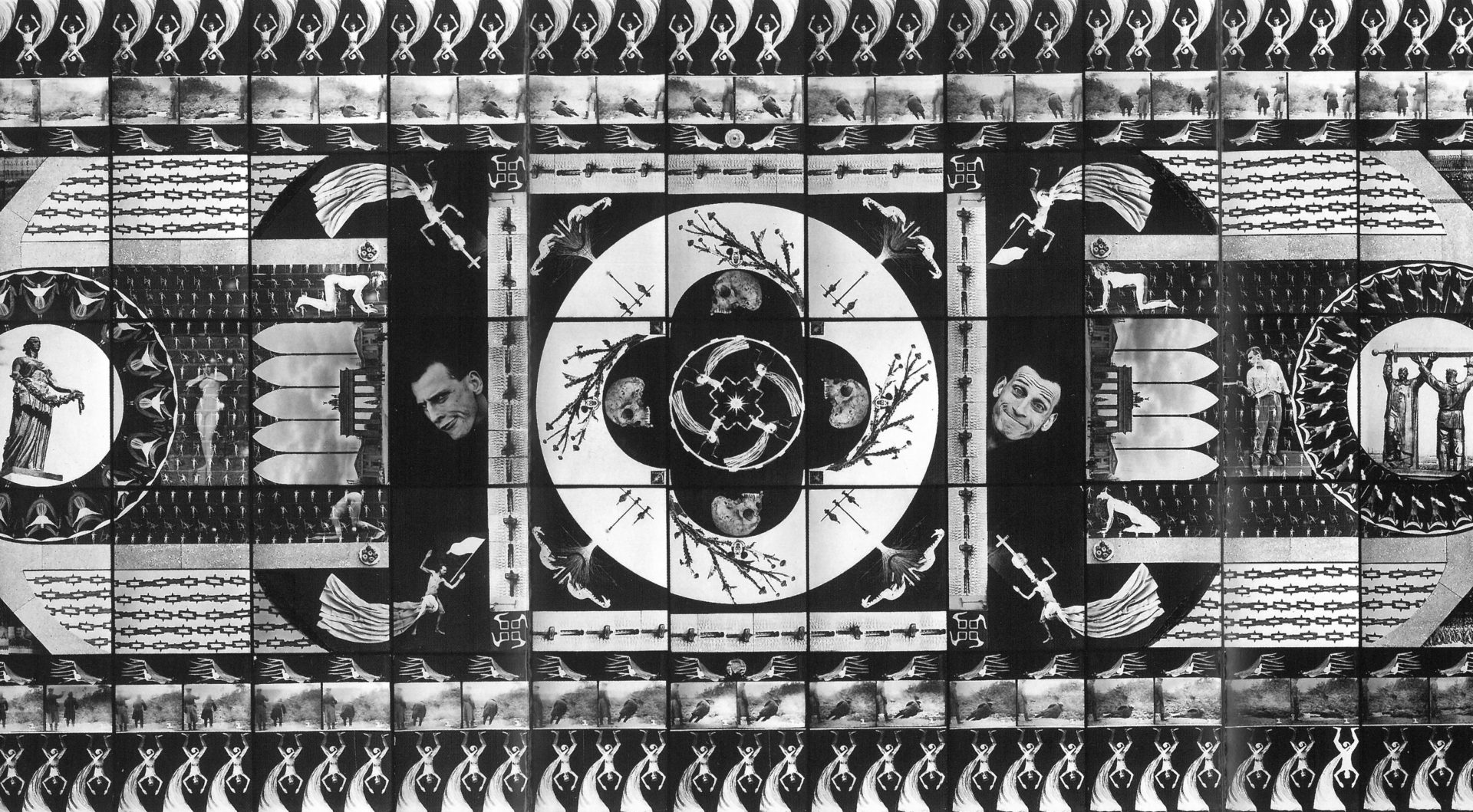

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850

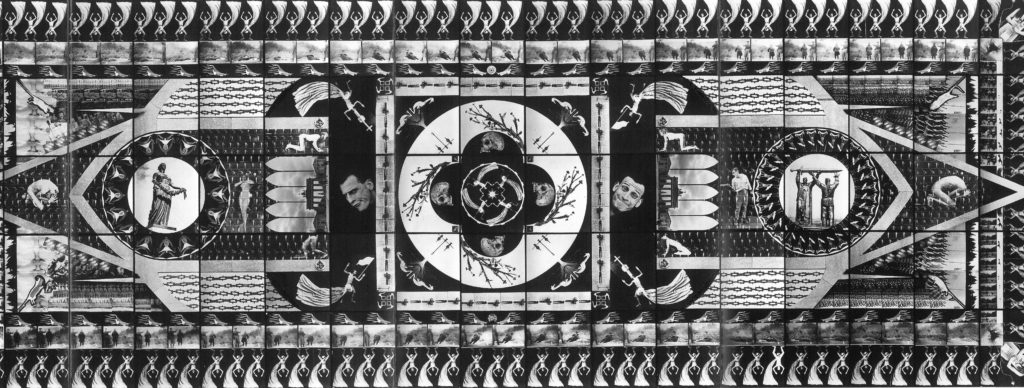

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850 (fragment)

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850 (fragment)

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850 (fragment)

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850 (fragment)

Zofia Kulik, “All the Missiles Are One Missile”, 1993, 300 x 850 (fragment)