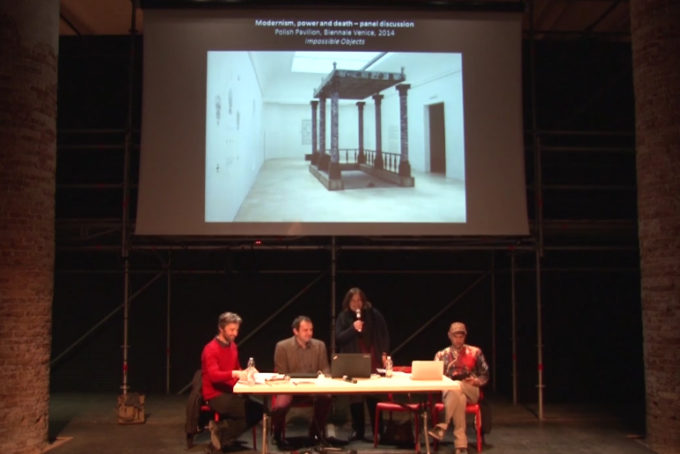

Impossible Objects

Created at the Polish Pavilion by the Institute of Architecture and Jakub Woynarowski, the exhibition Impossible Objects deals with the relations between modernism and politics in the context of building a modern nation state. The show’s highlight is a natural-scale replica of the canopy over the entrance to the burial crypt of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, the Polish political and military leader, created in 1937 at the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków according to a design of Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz. Several alternative variations of the canopy presented by the architect illustrate the process of arriving at a modernist form: from historicising loftiness to modern simplification. This is a literal stylistic absorption of modernism within a single object of small scale but complex symbolism. Embedded in the local context, the canopy is also an example of the self-contradictions characteristic for the European nation states that emerged after the First World War, torn, as they were, between an ambitious striving towards modernity and a rootedness in the rituals and myths of the past. The canopy showcases elements of official leader-cult propaganda, which has analogies in various European countries in the 1930s. Informed by the period’s classicising monumental modernism, the object’s style evokes the suffocating, xenophobic atmosphere of late-1930s Europe as it headed towards another devastating conflict.

The canopy is accompanied by large-scale drawings, created by Jakub Woynarowski, explaining the object’s specificity. The show’s narrative is also complemented by iconographic material depicting — through examples of the 20th century’s monuments, mausoleums and tombstones — the concatenation of power, modernism, and death.

- YEAR2014

- CATEGORY Biennale Architettura

- EDITION14

- DATES07.06 – 23.11

- COMMISSIONERHanna Wróblewska

- CURATORInstytut Architektury

Impossible Objects

At first glance, the drawing seems to be of a sketched geometrical figure. The eye begins to wonder in an attempt to follow the line but, in trying to retrace it based on what it knows about the representation, the mind loses track. Some of the elements seem to be congruent with the perspective but others push unexpectedly into the front, even though they should really be disappearing into the background. If a builder was given the task to construct such an object, no doubt he would simply give up. The figure is impossible. Both the design and its reality. Both the vision and its embodiment. Both the ideal and its convoluted shadow.In reaction to the question about absorbing modernity, which is the motto of this year’s International Architecture Exhibition, we have decided to move to the Polish Pavilion a baldachin known from the crypt with the sarcophagus of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, where it overlooks the entrance to the burial chamber at the Wawel Royal Cathedral. The model presented here is in a scale of 1:1 and differs from the original in its emphasis laid on the mannerist and astructural concept of its architect. Detached from the columns, the slab of the canopy seems to be levitating in air, creating a hallucinogenic, impossible figure.

Detail of the wrough-iron gate in the entrance to Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s burial crypt, design: Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, 1937. National Digital Archives, Poland

Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, the author of the baldachin, remains an anonymous figure in international discourse. Though he was a contemporary of Walter Gropius, and there are modernist patterns to be found in his designs, he was not a representative of the avant-garde. What is characteristic of his work, however, is a manner of referring to the past and regional motifs, which is reminiscent also of Jože Plečnik or Eric Gunnar Asplund. The Plečnik analogy seems particularly apposite here. Almost at the same time, both architects were employed to rebuild old royal residencies into modern seats of heads of state: Plečnik at Prague’s Castle, and Szyszko-Bohusz in Kraków and Warsaw. In the works of both architects there is also a specific suspension between modernity and classical tradition and, at the same time, a feel for the detail and composition. When analysing Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz’s designs, what is worth noting is the unique ability to construct symbolic figures. He transformed derelict castles and palaces or erected new public edifices and churches assigning to them all the power of a simple sign. In this clear language comprehensible to many, these buildings spoke on behalf of the nation or its leaders. The designs by Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, though absent from the broad discourse of modernism studies, seem to be of greater prominence in the history of the interwar architecture of Central Europe treated as a tool for creating nations.

Impossible Objects, visualisation of the Polish Pavilion exhibition, 14th International Architecture Exhibition, 2014. Rendering by Kacper Kępiński

His early schemes included an entrance in the form of a Gothic temple capped with a figure of hussar on horseback. The entrance that was actually constructed — completed in 1937 — is far less theatrical. A simple structure, it features elements which belong to the vocabulary of classical architecture — Corinthian capitals, balustrades as well as a Latin inscription (Corpora dormiunt, vigilant animae [Bodies sleep — souls keep vigil]) — but Szyszko-Bohusz composed them in an idiosyncratic fashion. The columns do not seem to perform their conventional load-bearing function: the massive slab fashioned from copper and bronze overhead sits on hidden posts. It seems to float above the descending stairs, as if denying gravity. The vertical lines of the columns continue ‘through’ the slab into six finials in the form of military crosses. Like his contemporary Jože Plečnik, responsible for the renovation of Prague Castle between 1920 and 1934, Szyszko-Bohusz’s approach to classicism was expressive and even idiosyncratic.

Plaque in memory of the victims of the Smolensk air crash, design: Marta Witosławska, 2010, Wawel Hill, Kraków, Poland. Photo by Anna Stankiewicz

The burial of the presidential couple at the Wawel Cathedral was a consequence of the logic of the mourning drama and was intended to unify a politically divided national community. But I am not interested here in the event’s political significance. What matters from the cultural perspective is something else: the funereal spectacle served the needs of the moment, dictated, as they were, by the mythological imperative of a patriotically solemn death. Here, as so many times before in the last two centuries of Polish history, it turned out that the mortal remains of great Poles do not end their existence in the grave but instead — and powerfully — become part of the symbolic universe. Freed from materiality, they begin to signify in a different order. The dead are no longer among us, but they hold reign over us. The tomb of the presidential pair has been made semiotically significant and it radiates outside. Corpses engage symbolically, exert pressure, cause people to act, divide and unite. One thing is certain: the dead continue to speak to us from their ‘living’ grave; we need them and they need us. It is us who set in motion these dead bodies from which the souls have departed. And it is the fate of the living that is primarily at stake here.

Interior view, Room of Honour, Polish Pavilion, World Expo, Paris, 1937, design: Bogdan Pniewski, Stanisław Brukalski, 1936–37. National Digital Archives, Poland

Similarly to many other politicians of his generation, it was obvious for the Marshal that in order to effectively fight the remnants of the past occupations, there was a need to create meanings, symbols and myths which would not only unite Poland and Poles, but which would also make it possible for the people to become a modern nation. The thinking outlined above was the motivation for bringing back to Poland in the 1920s the remains of national heroes who had died outside their homeland. Also new symbolic public edifices were erected. The story of the construction of the canopy over the entrance to Piłsudski’s crypt, presented here in a nutshell, is very much in line with the above policy, thus demonstrating how one of the most important myths of the Second Polish Republic was born in the last years of its independence. Charged with a strong emotional load recognisable to the Poles, the baldachin still remains a part of the semantic landscape of Central Europe — a region where new states were born and their identities were built after 1918. The form of the project is indicative of the efforts the architects had to undertake in grappling with the just developing architecture of modernity. At the same time, it is a reference to an important element of the modernist philosophy, which turned out to be particularly important in Central Europe of the interwar years — the focus is placed on the concept of the nation as a form, the construction of which was as if imposed from the top.

Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, design of the southern elevation of the Marshall Józef Piłsudski House in Kraków, 1932. Published in Architekt, no. 4, 1932

An insightful critic of modernity, Fredric Jameson, argues that modernity needs to be clearly distinguished from modernisation. The modern project is comprised, according to him, of two elements: a material-infrastructure basis (technologies, organisational models, machinery, equipment and so on) and a socio-ideological superstructure — a set of norms and values associated with modernity, such as equality, social justice, secularism and so on. Jameson calls the first component ‘modernisation’ and the second one ‘modernism’. Modernity, he believes, is a complex interaction between the two. The mainstream of Polish public opinion and its political class seems preoccupied chiefly with the material-infrastructure aspect of the modern project and does all it can to avoid the ideological one. Motorways, Internet, rapid transit, ATMs — yes! Emancipation of women, sexual minority rights, separation of state and religion, rational urban planning, reduction of material inequalities through active redistribution — no! This is not a way of building a modern society in Jameson’s sense, but rather a formula for modernisation without modernity. In this respect, Poland epitomises the whole region.

Anıtkabir — Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Mausoleum, design: Emin Halid Onat, Ahmet Orhan Arda, 1953, Ankara. Photo by Raskolt

This is how the memory is actually managed — by national holidays and anniversaries, statues and monuments — this is how the national identification is created. Therefore, monuments, even though they usurp a form evoking timelessness, immortality or, at least, longevity (which is proven by the material used — stone), are merely political products. The monument and its meaning are created in a specific time, place and as a result of a current political intention.

Jakub Woynarowski, The invisibility, 2014

An even more invisible and puzzling structure is the huge territory cut off from the rest of north-eastern German island of Usedom, and devoted by the Nazis to the production and the testing of rockets: Peenemünde. In my view, this complex is much more evocative of the relationship the Nazi regime constructed with architecture than the bombastic compositions designed by Albert Speer for Adolf Hitler’s new Berlin. The electric power station, the factories devoted to the production of liquid hydrogen or oxygen, and the halls devoted to the production of the rockets, many of which have survived to this day, are built in a sachlich language. Their concrete skeleton is left visible, as are the brick infillings. Walter Schlempp, a former member of Speer’s Berlin team, had designed a rigorous architecture, in order to accommodate a highly advanced technological program. Yet this rather elegant and sophisticated interpretation of industrial modernism was meant to remain totally hidden, out of sight of all the Germans, not to mention the other nationals.

Grave of Adolf Loos, own design, 1931, Zentralfriedhof, Vienna. Photo by Lucy Janes

From the outset, Poland’s entry into modernity was an antagonistic one, a confrontation with a force that offers possibilities but also destroys. For this reason, Poles’ attitude towards modernity has invariably been ambivalent. The modern order appears as something that has impressive achievements and opens vast prospects but, at the same time, inspires fear and hatred, for it destroys the traditional patterns of culture. Thus, modernity both attracts and repulses.

Marble pattern, canopy over the entrance to Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s burial crypt under the Silver Bells Tower at Wawel Hill, Kraków. Photomontage by PROPS

The new entrance to the crypt — usually described as a baldachin in reference to the cloth of state which covered royal thrones and beds of kings in the European tradition – marked Piłsudski’s status as a victor. It was fashioned from the trophies of war. The stonework was recycled from sections of granite plinth which had supported a bronze sculpture of Otto von Bismarck in Poznań until 1918. The six nephrite columns of Szyszko-Bohusz’s structure were salvaged from the St. Alexander Nevsky orthodox cathedral in Warsaw. Dedicated by the Russians to the pro-tsarist Poles who had been executed by insurgents during the January Uprising in 1863 and a clear demonstration of Russian power, the Cathedral had been built between 1894 and 1912 only to be dynamited, after much discussion and a few protests, in 1924–26. The octagonal bases and the Corinthian capitals of the columns were recast from steel from Austrian guns. The symbolism of salvage was clear: no longer serving Poland’s enemies, they were now doing duty to the great unifier, the Marshal. In the case of the nephrite columns, a further — perhaps more private — symbolism was at work too. The orthodox cathedral in Warsaw from which they came had been designed by Szyszko-Bohusz’s teacher in St. Petersburg before the First World War, Leon Benois. This expression of patriotism was also, perhaps, one of patricide.

Canopy and slab over the entrance to Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s burial crypt, design: Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, 1937, Wawel Hill, Kraków, Poland. Photo by Adam Engelman, Historical Museum of Kraków

The plate with the inscription is not set on capitals of the columns, but on small and hidden elements, thus leaving apparently levitating in the air. This division in the construction is accompanied by the following quote: Corpora dormiunt, vigilant animae (Bodies sleep — souls keep vigil). The canopy, seemingly reconstructed in a 1:1 scale in the Polonia Pavilion, reveals the rupture in an even stronger manner by the actual physical detachment of the heavy stone slab from the supporting elements. The effect thus is that the mannerist gesture of the impossibility of construction is strengthened, which in Szyszko-Bohusz’s design had separated the two orders: the worldly order and death from the eternal domain of the spirit. The classical organisation was thus reversed so as to mark a certain Romantic — or even a surrealist — logic. The genuine activeness was now in the land of the dead, whereas the dream was in the real world. When seen from this perspective, the canopy ceases to be a solid classical aedicule — the original construction to which both classicists (Marc-Antoine Laugier), as well as modernists (Le Corbusier) referred, and instead it becomes a dreamlike construct contradicting the principles of tectonics. The slim space, which has not right to be there in between the supporting and supported elements, contains a multitude of tensions which determine the symbolic character of the work by Szyszko-Bohusz. These are tensions between the classical order of columns and the abstract and modernist nature of the slab, between tradition and modernity, between worldliness and eternity, between the past and the future, between life and death . . .

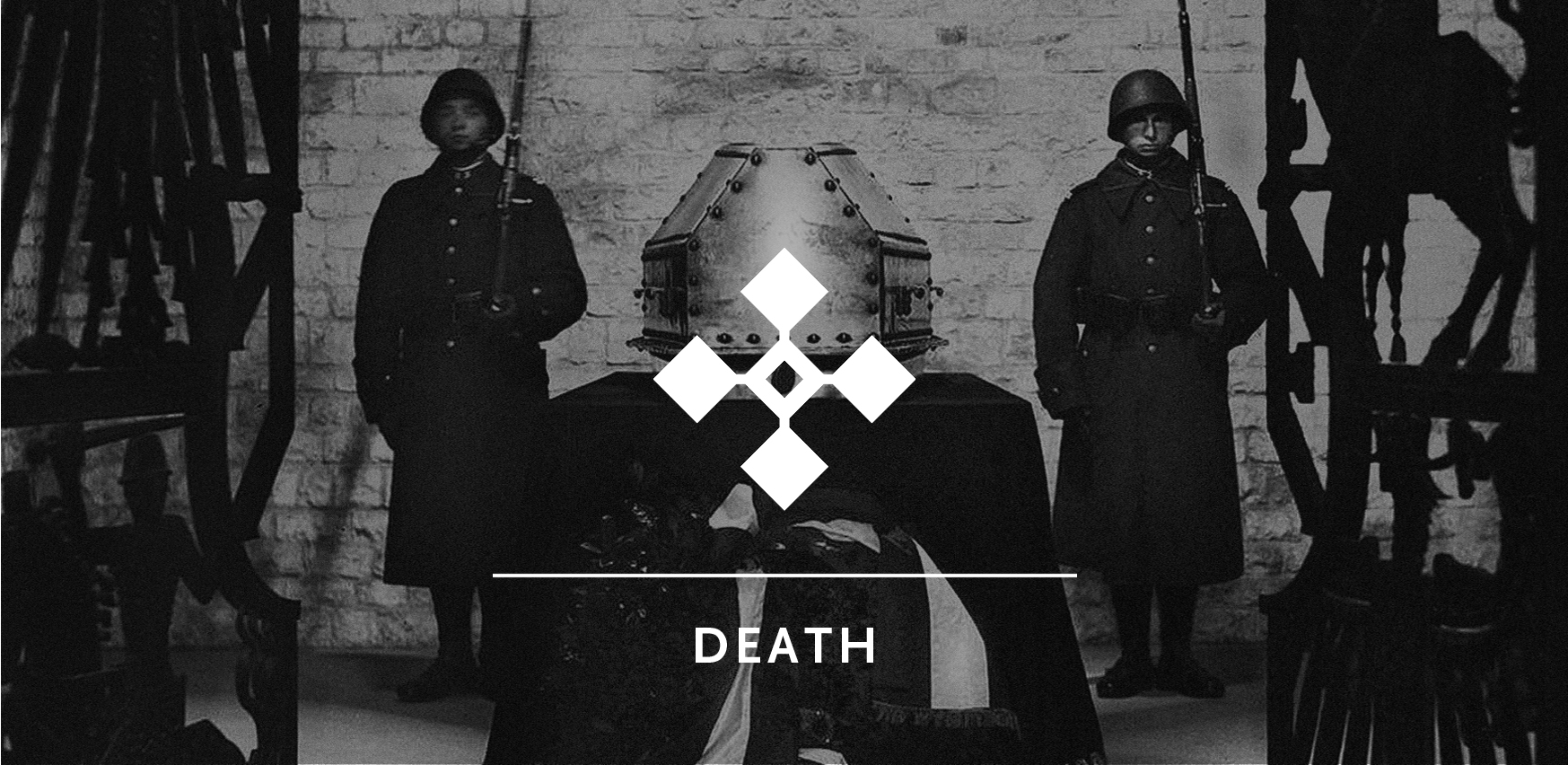

Guard of honour at Józef Piłsudski’s coffin, 1937, Wawel Hill, Kraków, Poland. National Digital Archives, Poland

There is no doubt, it seems, that a black thread of mourning runs deeply through the tissue of Polish life. This is true in many respects. From the specifically Polish model of Catholicism (strongly emphasising the theme of the crucified Christ), through public-space practices (the funerals of famous artists and political leaders, which become patriotic spectacles), to works of art (Polish theatre filled with the spirits of the dead, as is the related filmic tradition). Death may be a master from Germany but, as it turns out, he feels at home in Poland too. For over two centuries now it has been an indispensable component of our symbolic equipment, an ideational foundation of the Polish collective imagination. Death: a black flag under which — like under a wide umbrella — we can all take shelter.

Detail of the wrough-iron gate in the entrance to Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s burial crypt, design: Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, 1937. National Digital Archives, Poland

It was May 1935 when Józef Piłsudski died. This initially leftist activist, who had fought against the Russian domination in Poland, was the founder of the first regular Polish troops under the auspices of Austria. Piłsudski was able to achieve this in reaction to the outbreak of First World War, and when the war ended, he became one of the founding fathers of Polish independence. A growing conflict with the leaders of nationalist groups pushed the Marshal to orchestrate a military coup d’état in 1926, as a result of which he became a real, though not entirely formal dictator who enforced his ideas and strategies in a manner which was sometimes rather brutal. The almost full decade of Piłsudski’s rule, until his death in 1935, was a period of authoritarian power but also a time of progressing economic and social modernisation in Poland (as one of the first countries in the world, Poland introduced the right to vote for women as early as 1918). This style of modernisation with a whip in hand was maintained by Piłsudski’s continuators until the outbreak of Second World War. In the so called ‘rule of the colonels’, the cult of the Marshal was an important symbolic element, the focal point or the ideological common denominator of which was the location of the leader’s burial, and in particular the mausoleum arranged in the medieval Royal Cathedral at the Wawel Castle in Kraków — a pantheon of rulers, national heroes and artists. Buried in a specially reconstructed crypt, Piłsudski was to continue uniting the Polish people.

Read more in the exhibition’s catalogue

Authors

Curatorial team

Institute of Architecture is a foundation established in 2011 in Cracow which is engaged in the promotion of disinterested reflection on the theme of space through the organization of interdisciplinary exhibitions about architecture, publishing books, promoting architectural education and the popularization of architecture, mainly modern and contemporary architecture.

Dorota Jędruch (1977) — has a specialist interest in the problems of contemporary architecture (especially from a social perspective) and the visual arts. She is working on a doctoral thesis at the Institute of Art History at the Jagiellonian University on the theme Three Models of Social Architecture in the 20th Century France. Le Corbusier, Aillaud, Bofill. She works in the Education Department of the National Museum in Cracow. She was co-curator of the exhibition In-habitation 2012. Garden City, Gated City in the National Museum in Cracow. She is a member of the foundation Institute of Architecture.

Marta Karpińska (1977) — editorial secretary of Autoportret. Pismo o dobrej przestrzeni, a graduate of Art History. From 2009–2013 was editor of the monthly Architektura&Biznes. A member of the foundation Institute of Architecture.

Dorota Leśniak-Rychlak, PhD (1972) — chief editor of Autoportret. Pismo o dobrej przestrzeni. She is trained as an art historian and architect. Curator of the exhibition Charles Rennie Mackintosh in the International Culture Centre in Cracow (1996) and co-curator of the exhibitions: 3_2_1. New Architecture in Japan and Poland in the Manggha Centre in Cracow (2004) and In-habitation 2012. Garden City, Gated City in the National Museum in Cracow. The author of the introduction to a selection of texts by Adolf Loos, Ornament i zbrodnia [Ornament and Crime], Warsaw: Centrum Architektury, 2013. President of the foundation Institute of Architecture.

Michał Wiśniewski, PhD (1976) — a graduate of art history and architecture, is interested in the connections between modern architecture and politics. He works in the International Culture Centre and the Economic University in Cracow. The author of a monography of Ludwik Wojtyczko. Co-curator of the exhibition In-habitation 2012. Garden City, Gated City in the National Museum in Cracow and curator of the exhibition Reaction to Modernism. Architecture of Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz in the same museum. A member of the board of the foundation Institute of Architecture.

Artistic concept

Jakub Woynarowski (1982) — a graduate of the Graphics Department and the Interdepartmental Intermedia Studio of the Academy of the Fine Arts in Cracow; he currently teaches at the Studio of Narrative Drawing at his alma mater. He is a designer and illustrator, as well as a graphic artist, creator of comics, artbooks, visual atlases, films and installations. He is also an initiator of site-specific activities in public space. www.phantascope.blogspot.com | www.wernalina.blogspot.com